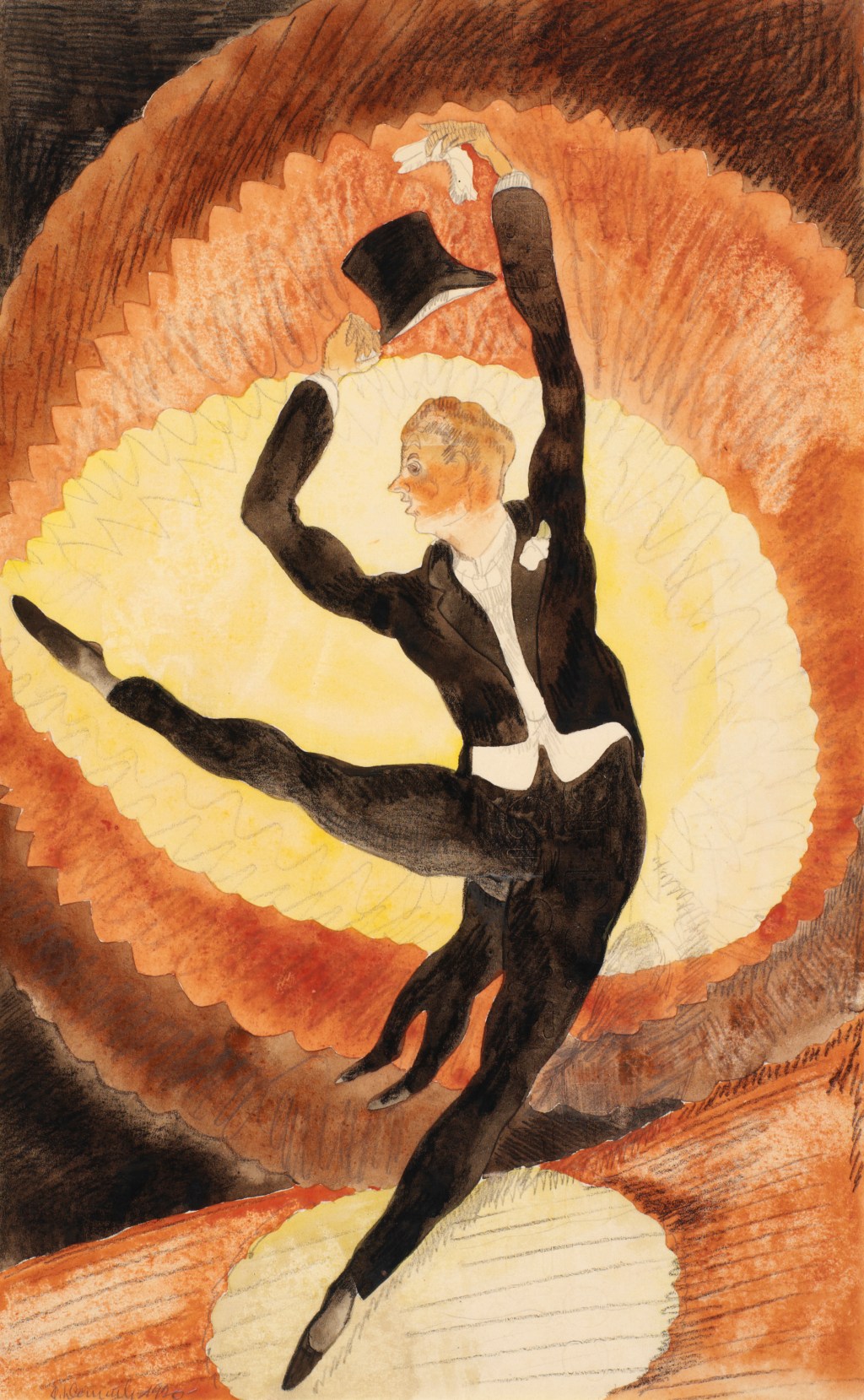

The mating dance, as you know, is meant for our own good, so we don’t mate by mistake with another species. You can tell by the way he dances.

It comes to bear upon women mostly, who, even on this first date, may suspect he’s not fully Homo sapiens. Possibly not even vertebrate. Maybe not of this earth.

Thus when Lo and Cluster plan for the homecoming dance she puts her foot down: Toe the line in the matter of complex ritualistic behavior. Wear a tie. Not the electronic dog collar Lo counts on to keep himself awake in class. Not the adorable knit kitty hat with copper wiring that broadcasts brain signals to a monitor in his basement.

It makes you wonder how people get together in the first place. Smiles, probably. Not all smiles are alike. We betray subtle distinctions face by face, unveiling where we fall on a scale: Snake? Weasel? Cute and fun to be with? Face muscles help us read people.

Except when the face is utterly neutral. Blank. Like a store dummy, which from time to time is our Lo’s demeanor. Which in turn makes Cluster smile. Which is how they meet. So already we see a feedback loop. All valid clues. Let’s move on.

This is about what a grandmother owes her granddaughter, and whether Grandma can deliver. Writ large, what one generation owes its successors. And whether cause and effect always work the same way. Might they reverse? Switch places? Does a smile induce the mating dance? Or a dance the smile? Does the knob open the door? Or the door turn the knob?

Cluster’s grandmother, Grandma Nana Lola, learns early in life she can open a lot of doors just by jiggling the knobs. Is she then condemned to be only an effect? The outcome of a string of bad boyfriends, awful dates and street fights?

Or can she somehow be also the cause of something favorable, finally, for her granddaughter, whom Grandma Nana Lola loves, truly loves?

Grandma’s name is Lola. Baby Cluster soon calls her Nana. So, Grandma Nana Lola.

Cluster? Not the best name, maybe, but let’s use it. Grandma negotiates this with her daughter, Cluster’s mother. Grandma gets to pick the name. Mom decides on the spelling.

Grandma Lola, deep in her fretful soul, struggles always with the unrequited certainty that she, Lola, is a wronged woman. Lola wants revenge on somebody for something. So for her daughter’s baby girl, Grandma Lola picks the name of a paragon among wronged women, a longsuffering queen dragged all over antiquity and beyond as the most wronged and most vengeful of wronged, vengeful women. Grandma reads about it in school and never forgets. For the new baby girl, Grandma chooses the name Clytemnestra. Mom spells it C-l-u-s-t-e-r.

Not a bad choice. The name of a bomb, true, which sometimes applies to Cluster. On the upbeat side, we’re all each of us a cluster, are we not? Cluster of this and that? Bad and good. Fair and drastic.

Moreover, within, we all have a little luster. We all have lust. For better or worse, we’re all stuck with us. So, Cluster. She’s fifteen now, tall, strong, thinking for herself.

Here’s the thing again, so pay attention. Can cause and effect reverse? Cluster turns out, as she grows, to be a gatherer, a collector. Hoarder, but sort of organized. Seeking shards of a shattered universe she calmly longs to rebuild.

Does Cluster hoard of her own accord? Or is her name to blame, creating kind of a psychomagnetic field for Beanie Babies and old Tarzan magazines? Her collection even includes a vintage Kiss poster that Grandma reviles. Does all Cluster’s clutter at some point take the initiative and cause Cluster to — cluster?

Grandma Nana Lola’s issues, on the other hand, seem to be straightforward cause and effect, a result of personal choices earlier in life. Teen queen Lola loves the music and doesn’t mind the boys in the band. Not Kiss, but every other band passing through the five-state area.

She hangs around after concerts, encounters an overwhelming array of arrant knaves, gets pregnant and hands the baby off to her own mother. A castoff groupie of yesteryear, she launches a second career as an office flirt. This suits her and she has a patient boss.

One day this boss gives her a big assignment: Draft guidelines on dress for casual Fridays. She gets this assignment because she’s an inveterate violator of workplace boundaries. She actually relishes routine summons to her boss’s office regarding — what is it today? Neckline dives too deep? Skirt slit too high? See-through harem pants again?

So Grandma Lola gladly seizes this assignment. Here let’s call her Lola, short for her full name, Dolores, which contains dolor, which means sorrows. Is her name somehow the cause of her sorrows? In any case, it explains why Grandma, years and years into the future, feels a deep connection with — you guessed it — our man Lo, more of which anon.

Anyway, assigned to trot down the street to a library, Lola looks up casual and finds instead the word causal. Spelling is not what Lola does best. She settles in to read about causality, efficient causation, teleology and more. Lola, you should know, just scraped through in high school but she’s actually pretty smart, dyslexia notwithstanding.

Here at the library, Lola seeks guidance on great looks for work, looks that stop men cold outside her beige cubicle, but with minimalist shoulder pads that don’t snag on the crazy corkscrew twelve-foot phone cord as she twirls and paces during calls.

She spends an entire morning at the library, sensing that her boss must be very into causation, which she takes to mean “casualization,” that is, transition to acceptable casual dress. Efficient causation is what she seeks, then, which must mean “working smarter, not harder,” her boss’s mantra. This involves teleology. Same as technology, right? An alternate spelling?

In fact here Lola’s instinct is on the button. Teleology means getting to some preset goal, such as her unit making its numbers for the quarter. All their work causes this preset goal. So the outcome, the effect, reaches back to cause all the preceding causes. That’s teleology.

Or losing five pounds. Here indeed we have an out-and-out reversal of cause and effect. The goal, the outcome, the effect — losing five pounds — reaches back in time to cause regular workouts in a fabulous Jane Fonda leotard, sweatband and floppy leg warmers, feeling the burn to the Jane Fonda workout tape, and then of course foregoing office donuts.

Come to think of it, teleology is exactly what we do with love, isn’t it? We create our own perfect mold, as for a bronze sculpture. Then we scout around for prospects who might fit. We pour in the molten metal of that first date — and it always slops over. Nobody fits.

Our man Lo for certain is too big to fit any mold that Cluster might be working on, if she has one yet, more of which anon again.

Back at the library, Lola thinks she’s done the job. Efficient causation. That sounds very businesslike. And here’s an expert, big-shot consultant probably, let’s see, Kant, Immanuel Kant, who sounds worried about a relaxed Friday dress code getting too relaxed. He thinks causal necessity is “a bastard of the imagination, impregnated by experience.”

Oh, ho! Lola muses. Bastard? So he’s pissed about casual Friday. She leaves him out. But Lola finds comfort in his reference to somebody else getting pregnant. She knows for sure now she’s on the right track. If it happens to somebody else too, getting pregnant, she doesn’t feel quite so alone.

o o o

We breed successfully, if we do, because we believe in regular causality, whether it exists or not. Will the sun rise tomorrow? We act as if it will. And we’re always right. So far.

If the sun rises, by the way, you men, remember to send her flowers. That always turns the knob. Lo and others of his ilk may discern this eventually. If the sun keeps rising.

But do cause and effect flipflop? Does the effect turn around and cause the causes? As with the flowers, the smiles, the knobs, the five pounds, the donuts and Jane Fonda?

Let’s say God does have a Plan. Who’s going to argue with it? The outcome of any such Plan is the Effect. And that Effect in turn, under this Plan, reaches back and creates all the Causes leading to that Effect. Ergo, Cause and Effect reverse. Done deal. Maybe it happens.

This is from Aristotle, the philosopher. Lola’s careful library reading and bad spelling lead her to believe he’s a philanthropist, a certain wealthy, generous Greek shipping magnate. Someone she’d love to meet, by the way, out on his yacht.

All this thinking makes her dizzy. She goes outside to smoke.

o o o

Grandma Nana Lola still treasures a ratty old copy of Rock Bottom Magazine. She points carefully to the corner of a grainy crowd photo from a long-ago outdoor concert. “Look!” she tells baby Cluster proudly. “Can you see it? That’s my breast.”

Little Cluster is sick with a cold in Nana’s lap, in the new bright yellow wingback recliner Nana calls her “cheer-me-up chair.” Baby Cluster leans her nose into the page to see. Grandma carefully wipes off the page.

It was the tall guy, the very tall one. Might have been a drummer. Or bassist. She doesn’t remember his name, or the band. We’re talking about the 70s. Who isn’t in a band?

Anyway, Lola gets pregnant and hands off the baby to her own mother to raise. This baby girl grows, blossoms, rebels, gets pregnant herself and hands off another baby, her baby, to her own mother — Lola, in whose lap this latest baby, Cluster, now squirms and snuffles.

Lola’s own mother, Cluster’s great-grandma, who starts it all, lives to be ninety and gets a chance to hold great-grandbaby Cluster at the nursing home, just after she’s born, in her old blue hands, with all the love of the ages in her failing eyes.

Lola finds this deeply moving. Treasures it, as much as the magazine crowd photo of her naked breast, if not more. We reach a point in life where all this starts to matter.

o o o

As Cluster develops into a tall, capable young woman, Grandma Nana Lola’s motherly protective instincts mount to a climax, and bitter memories about men slash to the surface. Lola begins to want her granddaughter to know about men. Tall men especially.

The trigger is when Lo pops up, head and shoulders over everybody else. Then Lola knows it’s time. She carefully rehearses a set of incontrovertible guidelines for Cluster, yet to be voiced: Stay away from tall guys. Or take them over, utterly.

Thus Grandma Nana Lola begins the dance. With Lo. Is it a sort of pre-mating dance? Or a post-mating dance? What can it possibly cause?

Cluster’s Grandma, even now, in late midlife, well remembers her long-ago library morning of complex thinking about casual dress and causation. What she finds then she believes still — and applies.

Teleology? Is there a Plan? If something is meant to be, you might as well relax. You can’t help how it turns out. If it’s meant to be, the effect is in place before the cause gets going. Not your fault. Not anyone’s. You just get on the bus, climb into the top bunk and go for the ride.

But if there’s no Plan — Lola has much to do, then and now. She tells no one these deep thoughts. Cluster, busy with school and friends, is in the dark about it. In the dark is where cause and effect operate most decisively, forward and backward.

o o o

Here let’s re-introduce Lo. Luther Odysseus. Fifth graders learn his middle name and call him O.D. Or just Odd.

Luther Odysseus ignores this, and by high school people come to know him by his initials, L.O., always now foreshortened to just Lo.

We must go to Lo to understand why Cluster is drawn to him, yet keeps him at arm’s length. Lo is six-foot-eight and plays the triangle in band, sometimes, or other percussion instruments requiring nothing more complex than banging and crashing.

Years earlier, as Lo reaches six feet, Dad demonstrates basketball. But Lo doesn’t fully understand gravity then yet – still doesn’t — and hand-eye coordination during growth spurts is just too much to ask.

In high school Cluster does her best to ignore Lo at first, but eighty inches is a lot of teen-ager. As we meet Lo, in Home Economics class, he stands tall and quavering, thinking deeply, glazed, looking out the window but not focused on anything, as though he’s trying to guess his own weight.

Cluster examines him from the next seat. She’s here to learn decluttering — organizing and optimizing her space.

“Look!” Lo suddenly tells Cluster, pointing out the window. “The universe is holographic. Every shard of being contains every other shard of being.”

She says, “So your room is a mess too?”

Reading between the lines, this means she’s inviting him to come see her room. Or inviting herself to go see his. She may or may not realize this. What’s causing what here, anyway? Certainly Lo reads nothing into it. In any case, Grandma Lola’s flirtatious genes writhe and wriggle just below Cluster’s authentic veneer of sensible awareness.

Meanwhile, if Lo’s right about the universe being holographic — if every shard is right up next to and even within every other shard of being – can cause have any meaning? Whatsoever? Things come and go as they please. Wouldn’t you say?

In any case, Lo all but ignores Cluster at first. Boys languish always well behind girls in terms of maturity. Lo won’t realize Cluster is flirting, if she is, until he’s, oh, maybe, late midlife himself. Just now, he’s fixated on how his brain works.

Luther Odysseus? That makes him Rebel and Wanderer. Joyous Mom and Dad decide this at his birth. It turns out to be exactly right. Little Luther Odysseus rebels routinely against normative behaviors and his mind wanders all over creation. He’s in Home Ec to learn to knit.

Lo is fine, not special needs or anything, just creative. Maybe he’s a victim of too much parental encouragement. He stays up late reading, thinking, fiddling with electronics and computers. Sleep-deprived like all teens, some days he wears his dog collar, the one he made for himself. When he dozes off in class it delivers a discreet 400-volt electric shock to the vagus nerve, right there in the carotid sheath along the neck. It’s sound-activated. He snores.

Lately, though, he prefers his adorable knit baby-blue kitty hat, with holes for ears. Cat ears. A fledgling at needlecraft, he doggedy knits this himself, from a pattern posted by an overmothering cat lady somewhere.

The kitty-hat backstory is truly inspiring, a towering monument in the passing landscape of science. As you probably already know, researchers take great interest in what cats are thinking, unlikely as that seems, and these inquiring minds — the scientists, not the cats – these inquiring minds learn not only to knit these kitty hats but to weave in wires among the fibers of such hats in order to pick up signals from cat brains. To see what cats think and whether to do anything about it.

Cats are just smart enough to paw off ordinary patch sensors. But some cats, science finds, condescend to wear these oh-fer-cute kitty hats around the lab.

Our man Lo, reading this someplace, conceives such a wired woolly for himself in order to study his own brain, which, as you begin to suspect, is often beyond reach without special accessories. Before he finds out about kitty hats, he works on a helmet extruding an array of antennae, but these protuberances snag on low-hanging branches and interfere with police radio. As soon as Lo learns about knit kitty hats he gives up the helmet idea.

The kitty hat entirely fetches his fancy. Lo’s Mom, ever nervous about his basement lab work, nevertheless actually even helps out on this one. He orders the electronics and Mom gets him started. Weaving in the wiring is harder than it sounds. You need an Icelandic bind-off at every voltage doubler. There is some fire risk.

In addition to the wired baby-blue kitty hat itself, Lo is particularly proud of his rough-and-ready interface between wired hat and his seat-of-the-pants computer neural network. He programs it with deepfake capability and finds old videos of himself in eighth-grade gym, swimming at camp, doing the Floss. Remember the Floss? A dance move for 12-year-olds that looks like brisk toweling between the legs?

When the big moment arrives, Lo straps on the kitty hat, crosses his fingers, throws the switch and studies the big wall screen to see what he’s thinking.

It works. The damn thing works. Lo hollers and knocks something over with a clumsy touchdown dance. Dad hurries downstairs and sees Lo thinking about playing basketball. It shows on the screen. Dad looks from screen to Lo to screen and back and joins the dance. Lo’s good! In his mind, at least.

Neighbors are picking up the signal as well, on their TVs and phones. Later they congratulate Dad on Lo’s great ballhandling, aggressive rebounding and flawless shooting. He looks so natural out there, they say, with that between-the-legs dribble.

How come Dad never brags about this? And why are these highlight videos playing on their phones and TV screens?

Even Mom comes downstairs, but she’s always afraid Lo will fall as usual and hurt himself, that is, in this case, think about falling, so she watches for a moment, gives him a big, proud hug and then goes back upstairs.

Damned if it doesn’t work. It really looks as though the TV is reading his mind. Of course maybe he’s a weasel charlatan rat and does this by stealth, by AI, with neural networks and deepfakes, without thinking anything at all. It crosses Cluster’s prudent mind.

o o o

Next week, back in Home Ec, Lo in fact does indeed finally notice our Cluster and does indeed invite her to his house to see all this. Mom has cookies and coffee ready. Mom starts pushing coffee at about age eight, hoping to stunt Lo’s growth.

Cluster, Lo and Mom go downstairs to see Lo’s setup. He explains at length. Mom soon fogs over and goes back upstairs. In her absence, Cluster grows wary. She and her girlfriends routinely discuss at length how to deal with boys, in every situation imaginable.

Lo shows Cluster what the neuronal output looks like on the screen when he’s daydreaming, when he has to go to the bathroom, when he hits his head on something. When he’s thinking creatively. When he’s thinking procreatively, as growing boys do.

At this, Cluster goes from alert to action. She studies the monitor a moment and then turns to Lo. Tall enough herself to go upside his head, she gives him a good, hard slap.

The monitor jumps. Lo recovers his footing and checks the screen. “It works!” he exults. “Do that again!”

They hear a vigilant footstep on the stair. “Everything OK?” Mom calls.

o o o

Back at Grandma Nana Lola’s, Cluster mentions that the universe is holographic. That’s what this boy says. Not her boyfriend, she emphasizes, but a boy, and a friend. This boy says that every shard of being, every sliver of space-time, is right next to every other shard. Every shard is even inside every other shard, Cluster explains.

To Lola, this sounds familiar, far too familiar. Love talk from a weasel.

Nevertheless in this shard idea Grandma Nana Lola finds hope for herself. Does it mean that she, Grandma Nana Lola, sitting here in her yellow worry chair, can reach back and hip-bump one of her bad choices — say, the tall drummer — right out of the top bunk there on the rock-band bus? Plunge him headlong into the aisle? Not get pregnant?

But that tall drummer brought about her beautiful grandbaby Cluster! And joy to Great-Grandmother’s old blue eyes, there in the nursing home.

In the human cortex lurks the source of complex thoughts — of intent, of will, of desire. In particular, this interface bears upon our question. Can causation reverse? Thought contracts muscles, muscles activate arms, arms shoot baskets and draw lovers near. Straightforward cause and effect.

But which is which as Lo watches himself think? He knows the ball is going through the hoop. Are his thoughts the cause? Or effect? And as Grandma Nana Lola aspires to recast her own poor choices, bunk by bunk by bus by bus — which is cause? Which is effect?

o o o

It’s movie night. Cluster and Grandma Nana Lola, on the sofa together, watch a girl and boy trapped in a gazebo during a violent rainstorm. What do the girl and boy do? Dance? Kiss? Sing? Depends on the movie.

It’s an example of complex multiple effect and multiple cause: Gazebo and rain combine to cause kissing and dancing, except it’s all in a carefully planned movie, teleology at its finest. There’s a plan, the script. It’s all going to happen this way no matter what.

When boy and girl finally do kiss in the movie, in the gazebo, in the rain, Grandma Nana Lola turns to Cluster. “If a boy ever tries that with you,” she cautions Cluster, there on the sofa beside her, “you can give him a good hard slap upside the head.”

Cluster looks at her with the shocked disapproval of a normal, brooding teen-age girl interrupted while she’s brooding and disapproving about something else. “Nan,” she says patiently — it used to be Nana, but that sounds like baby talk and Cluster is all grown up now — “Nan,” she says. “The girl wants to be kissed.”

As we see in the previous section, Cluster is a step ahead of Grandma Nana Lola about going upside a boy’s head.

“Nan,” Cluster adds, “sometime would you like to meet a boy I know who has an interesting science experiment in his basement?”

Oh-ho! Here it is. Lola’s moment of reckoning. Payback time for Grandma Nana Lola. Time for her to be the Effect that reaches back to Cause something better for her poor little baby granddaughter who is now almost all grown up. The wages of sin. Of the ages. The generational debt. Unwittingly this tall new guy in the kitty hat triggers the question. What does Lola owe?

“How tall is he?” asks Nana Lola. “And is it a finished basement?”

She means, is his bedroom down there.

“A little taller than me,” says Cluster, who is tall herself. She thinks old-fashioned Nana wants to be sure she’s not dating a shorter boy, a match frowned upon in certain circles.

“And,” Cluster adds, “it’s a comfortable basement.” Cluster remembers Grandma Nana Lola hates spiders. Cluster thinks it’s about that.

Grandma Nana Lola decides she better come along.

o o o

If Grandma Nana Lola now is an effect, an outcome, can she reach back and cause something more effectual than a street fight? Turn things kitty-wumpus, ass-over-teakettle for the better? Set things right? For her own troubled conscience and for her beloved lifetime legacy granddaughter? If so — how?

Cause and effect do work both ways, but only if you’re paying attention. When you’re not looking, they flipflop all over creation. A waste of good philosophy, for all we know. Maybe philosophers should just shut up and lose five pounds, in leotards and floppy ankle wraps.

Meanwhile, can you read faces? Look at Cluster. Would you hire her? She has a competent manner, strong features. She’s sure of herself, with a winning smile. Is she still smiling? At Lo?

How about him? His next project is electronic pants. Would you buy electronic pants from this young man who sometimes looks like a store dummy?

o o o

If Lo is right about each shard in the universe enfolding all the other shards, it means that all along Grandma Nana Lola looms ever nearer to one particular Effect. Her Outcome. Where she fits in The Plan. If there is a plan.

Is she close? Does she need but a nudge to reach the Effect toward which all her enfolding chaos of causes pushes her?

Is it ever too late? Can you always still change what’s done? Can she identify one more move to push toward and apply herself to the great and lasting benefit of her beloved Cluster?

Oh, the pants. Lo has trouble putting on pants. It’s just such a long way down. So Lo’s working on an idea for pants that put themselves on, integrating shape-memory chemistry, robotic soft-muscle technology and a kind of underpowered wind-tunnel suction effect. The design is still in his mind, and, of course, this means he can show anyone on his basement big-screen TV, just by thinking.

Cluster, with Grandma Nana Lola and Lo’s Mom, reluctantly agree to take a look at this project, in the basement, on the monitor. Mom covets any chance to swell with motherly pride — even if it means seeing her little son take off his pants in front of two other women, on the big screen. And then see the pants putting themselves back on, as per how he envisions all this in his brain, while he wears the adorable kitty hat.

Mom is especially proud of this cap. “Isn’t it just the right color,” she tells Lola. Grandma Nana Lola focuses on the pants, in which she finds great significance. Indeed, she offers a suggestion: His & Hers remotes, so the girl can press a button and put the boy’s pants back on if she changes her mind midstream. Before it gets too serious.

The suggestion is brilliant, is it not? Out of the blue? A shard of lightning? Lola knows not whence it originates. But exactly the right shard at exactly the right nanosecond. Maybe there is a Plan.

Lo loves this idea. For Mom, however, it’s all she can do to flee upstairs, weighing whether to invite Lola along, deciding against it.

Lo calls them Vortex slacks. His tagline is innocently lurid: Pants that put themselves back on. Watch for these pants. They’re an outcome.

Sensible Cluster however puts her foot down again: Normal dress slacks at the homecoming dance. Not these Vortex slacks.

Unless they transform into dancing pants. Just in case it turns out to be a mating dance.

o o o

Late in life, still in her cheery bright yellow worry chair, Grandma Nana Lola thinks on these things. It’s a drowsy midday in the winter sun. What is Lola, really? A fully realized, complete, castaway groupie? A retired office flirt — one of the best ever, if there’s a Hall of Fame for that? And Grandma Nana Lola to an all-grown-up, tall, sensible young woman.

Somehow, notwithstanding Grandma Nana Lola’s foibles, peccadillos, indiscretions, improprieties – in spite of all that — grandbaby Cluster is on a right track. With a tall boy, yet.

That makes Grandma Nana Lola at least, at last, a favorable influence. The monotonous cycle of passing babies back a generation, from grandma to grandma, of getting pregnant and leaving baby on grandma’s doorstep: that cycle is broken. Bent, anyhow.

And meanwhile, she, Grandma Nana Lola, an indispensable ratchet in that cosmic wheel, has verified, has corroborated, has witnessed — that matriarchy works just fine.

Either way, there is a plan. It’s a casual plan.

And she, Grandma Nana Lola, is in it.

Her role? To be an example.

A bad example.

Grandma Nana Lola nestles into her frayed, careworn yellow worry chair, in the window brilliant with winter sunshine, and there she falls asleep. She’s smiling.

###

Marc Hequet lives in St. Paul, Minnesota USA

Leave a Reply