I wandered into town in the midst of a solemn sunset. Autumn had not yet come to wrap the skyline in its burnished hues, but the blues of late summer had already faded weeks before, leaving everything cool and grey. It made roaming for work a listless, ethereal state of being, but was a welcome change of pace nonetheless. I was not able to afford a watch in those rambling years, and the one my father had gifted me at my acceptance into law school had stopped working after only a couple of years. Time often meant nothing on the road, but the hole I felt in my gut that evening told me that it must have been close to mealtime.

Although I was still quite new to the lifestyle at the time, the preceding months of walking the highways had acquainted me with a simple protocol for finding the necessities. First, I would make sure to hit the streets in times of heavy traffic, paying special heed to the comings and goings of locals. Where they departed might be an opportunity for some quick work. Where they went would almost certainly lead to food. In particular, I would set my sights on the rough, workaday folk that a more urbane traveler (which, I admit, could have described me only a short while before learning the way of the vagabond) might be inclined to overlook. These types were the most important, as they could be relied upon as a sort of tip network for my kind.

Such advice, in fact, led me to the site of this anecdote. A brutish dock foreman on the southern shore of Lake Michigan had told me that there might be some easy scab work over at an automotive plant in Tennyson, just a full day’s walk or an afternoon’s hitch southwest of Chicago. Scabbing wasn’t ideal, especially with how angry the strikes could get in those days after the G.I.s came home, but work was work.

The buildings of Tennyson were unimpressive, but far from the worst I’d had to pick from in the Midwest. There was a decent enough mix of tidy mom-and-pop establishments and the more utilitarian factories and mills that had come to color that point in my life. Where I had come to expect the hoarse blowing of rusted quitting-time whistles and the sputtering backfire shots of the ubiquitous hand-me-down jalopy, however, I was met only with silence. The town lay utterly desolate, marked by the kind of rarefied emptiness one might normally experience in hotel lobbies or hospital corridors, with their acidic lighting that permeates every inch of the space so you can be certain of your perfect isolation.

A half-hour’s walk brought me into what was ostensibly the town center. I stood alone amid a small, neatly manicured park, loomed over by a tall copper statue of what I assumed to be the town’s founder. His dress reminded me of those austere photographs of forgotten Civil War generals, their scarred, ropey bodies masked by big coats and epaulettes. What once may have been a strong chin and prestigious brow had been left to erode in the elements, giving the statue’s face a disquieting anonymity. The smooth remnants of its visage gleamed in what remained of the lowering sun, a far cry from the slowly creeping turquoise that had begun to oxidize the statue’s feet and legs. While the rest of the park was shaded with the stretching silhouettes of nearby buildings, the shadow attached to the statue’s feet seemed much darker and heavier, as if you could fall right into it and be swallowed by its inky depth.

As I turned my eyes from the sculpture, I was stopped by the distant gaze of a young boy. He seemed to be alone, so I took a seat on a nearby bench and hailed him. He waved in response and jogged his way over, joining me thereafter on the bench.

“Heya, mister stranger,” he lisped. “Don’t remember seeing you around here before. You new in town? What’s your name?”

I told him that my name was Ashley (at which he stifled a snicker, for I was among the last of the dying breed of male Ashleys) and that I was a traveler. Further, I had dropped out of law school a few months prior for unimportant personal reasons, and was working where I could as I slowly made my way back home to Washington state. He didn’t seem to have an immediate idea of where that was, so I gestured broadly toward the sunset for his sake. I said that I was going to visit my ill father, but didn’t have the means to take a train, or, heaven forbid, an airplane. Truthfully, I wasn’t eager to return to my family in those days. A number of mounting conflicts had formed like stalagmites between my father and I that, looking back, were ultimately insignificant, but I decided in the moment that this was better left unsaid, especially to a strange young boy. He nodded, and I asked him about his own parents.

“Well,” he started, putting his hand to his chin and looking skyward. He was clearly old enough to know the danger of talking to strangers, but perhaps still young enough to not know why. Something in him acquiesced. “My mama’s at home, probably, she should’ve just got off work. My daddy’s not around right now, though, because he’s fighting the Reds in Ko-rea!”

He melted into a gap-toothed grin, eyes gleaming with ignorant temerity, and we sat in silence for a moment while he came down from the throes of the longing daydream playing across his face. When the pause had begun to outlast its inciting conversation, I ventured to ask the boy why the town was so barren.

“It ain’t empty, mister. Everyone’s just inside. Most folks don’t go outside this time of day.” He said it as if it were the most obvious thing. When I inquired as to why, he allowed a look of puzzlement to overtake his earlier pride. “You’re really not from around here, are you, mister? Shoot, come with me. It’s just about to happen, anyhow.”

The boy leapt off the bench and tugged at my ragged coat sleeve before running off behind a shuttered drugstore. I followed him at an appropriate distance, and after a few minutes’ travel, we arrived in front of an elementary school. Its façade was one of the fresher sights in town, as its dappled red and orange brickwork had not yet given over to time and weather. The boy placed himself squarely in the middle of the building’s front stoop, and bade me join him. We waited there a short time, perhaps only a minute or two, before something unusual entered our sights.

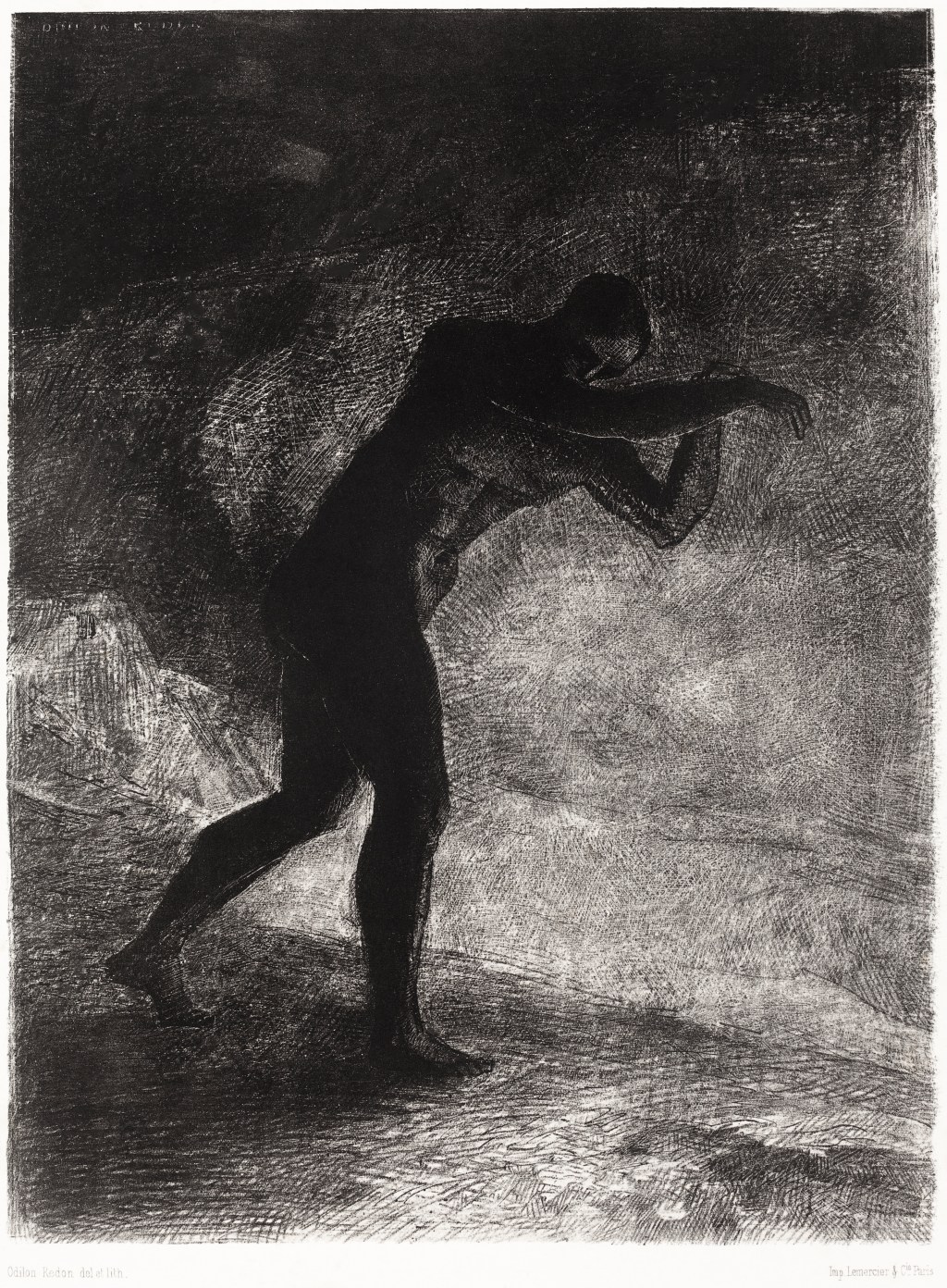

A figure rounded a corner at the far right of the schoolyard, then ran at a measured pace down the road across our vantage point and continued its path until it rounded another corner at the opposite end of the street, vanishing from view. The sequence of actions was utterly mundane, but the figure itself was unlike anything I had ever seen. It was noticeably taller than the height of a normal man, and its masculine physique resembled that which one might expect from the Apollonian sculptures of antiquity. I may have simply written him off as an impressive athletic specimen, save for two striking oddities. Firstly, its color resembled that of a pure silhouette, a humanoid gloom come detached from its corporeal double. Secondly, the thing had no shadow of its own.

The absurdity of it all did not hit me until well after the figure had disappeared. I had heard many campfire stories and tall tales of this sort from my fellow travelers, but only ever took them as a kind of escape from our mutual yearning for a life better lived, a clinging to the notion that amazing things could be found anywhere if one looked closely enough. Seeing this errant specter before me, however, I then understood that there truly could be so much more beyond my sphere, that a previously unknown world of secrets had been laid bare before me.

I looked back at the boy. That boundless grin had returned to his ruddy face. I tried to stifle my anxiety, lest the boy take me for some uppity tourist. I swallowed hard and questioned him about the passing figure as casually as I could manage.

“It’s pretty nifty, right? He’s our own little mascot, guess you could say.” Like the grin, his earlier boastfulness also returned. “We got all sorts of names for it, too. My mama calls it the Soul of Saint Sebastian.” The boy’s lisp made pronouncing this name a Herculean trial, but he soldiered through it. “Pastor Jim calls it the Harbinger of the End, says it a divine watcher come to show us our sins, but no one likes that. One of the teachers at school calls it the Rushin’ General. I always liked that one. My uncle calls it Spooky Babe Ruth, but Mama always tells him to hush up and stop playing a fool. Most of the kids at school, though, we just call it the Runner.”

A simple name, I thought, but one that does the job. The more plainly the boy spoke about it, the more I began to wonder if I was truly being as silly as he seemed to think me. I asked him to elaborate.

“Ain’t much to tell, mister. Couple years back, the Runner just showed up in these parts, no explanation or nothing. Runs down every street in town, same way, same time, every day. Never stops for anything, never bothers anyone. Goes somewhere else when it’s done. Gives some of the old folks the heebie jeebies, but most of us don’t mind it too much. Ones that do say it’s gonna be the death of us, it’s ruining the town, you name it.” He hooked his thumbs into his pockets and rocked back on his heels. “Me, I come watch it run by every day. My mama don’t like it much, but I don’t know why. Wouldn’t you come watch, mister?”

I felt like he was testing me, but a satisfactory answer eluded me. If the Runner travels the same path each time, why bother watching every day? I posed the question to him.

He gave me a grumpy, dismissive wave. “Ah, you’re just like the rest of them. You just don’t get it, do you, mister?” He plopped back onto the stoop. “Runner’s what makes this place special. Just because you get used to it being here doesn’t mean it ain’t special.”

I knew what he meant, but I couldn’t shake the feeling that he still knew something that remained hidden to me. The sun had fully set by then and the pre-autumnal chill was creeping ever deeper into my bones. So I made the boy an offer. If he could convince his mother to put me up in her home for the night, I would accompany him to watch the runner again tomorrow. It was far from the deal of the century, but it was too late to start looking for work, and the kid seemed lonely enough to appreciate the company. He smiled, hocked a loogie into his palm, and offered to shake on it. I had sealed deals with worse, so we made our pact and ambled homeward.

#

When I awoke late the next morning, the boy, whose name I had learned over supper was Jeremiah, and his mother, Minnie, were gone to school and work. This was typically a terrible blunder when putting up boarders, but I suppose I had made a good enough impression to warrant a lowering of guard amid these strangers. People were different back then, for better or worse; I imagine drifting must be nearly impossible in today’s world. In any case, I began to dress for the day and realized that the tread of my boots had finally worn completely off. It would be only another week or two before the soles began to bear the characteristic holes of the road, then give way to trench foot and frostbite. Finding quick work suddenly went from a necessity to a priority.

I had intended to follow up on the auto plant lead from a few days prior, but an overwhelming lethargy left me without the inner resources needed to canvas the town. So I elected instead to greedily burn my last dollar on lunch at a local diner, complete with coffee and some regional award-winning pecan pie. My stomach relaxed in anticipation of the luxury, or at least what I had come to call luxury. How low the bar can sink in thinner days. The townsfolk seemed oddly calm for people being set upon by a tireless wraith on a nightly basis. Beneath this placidity, however, dwelled a darker air, a kind of timorous knowing. Of what, I was uncertain. The sky was clear, but some hidden density shrouded the town.

As the afternoon drew on, I was surprised to find myself looking forward to the planned rendezvous with Jeremiah. The sheer strangeness of the Runner had nearly slipped to the back of my mind as I made my way back to the town’s central plaza. Just as the day before, I awaited the boy’s return on the cold stone bench. While I sat, however, I noticed a certain shift in the town as evening crept closer. As offices closed and people went through their day-end routines, a distinct melancholy spread over the faces of the citizens. It was as if the arrival of twilight had pulled a curtain over their hearts, signaling not only an end to the day, but to something deeper. In the growing silence, I turned my attention again to the park’s statue. The imposing figure’s smooth features seemed to observe everything in Tennyson, from the tired comings and goings of its lifelong inhabitants to the more memorable happenstances that would become the cherished dinner table stories of future generations. All of this, seen through that imperial eyeless gaze, must have seemed so quaint. But something in that primal corner of my mind screamed out at the smallness of it all, as if this space had refused to budge in the century since its founding, and would remain forever trapped in the morass of its own memories. The sun seeped lower into the horizon, and I again witnessed the statue’s shadow take on its disturbing, cavernous aspect.

My perception remained fixed on the oppressive presence of the statue until Jeremiah, red face and dark curls ablaze in the dying light, returned to the site of our initial meeting. He beckoned me in the direction of the school, excitedly flapping his tiny hand back and forth, and we made haste to our lookout with a sort of unspoken resolve between us. We took our positions: Jeremiah bent on one knee, I seated on the edge of the stoop, back arched in trepidation.

Again, only a few short minutes passed in silence. As the sun completed its dip below the edge of Tennyson’s humble buildings, the Runner made its scheduled appearance. Looking closer this time, I realized that the entity did not have a face of any sort. Its head was utterly smooth, devoid of any visible features. Its body, meanwhile, appeared in much clearer definition, as if it had begun to move in slow motion, allowing me to fully absorb the true nature of its form. My stomach turned. While it initially appeared mannequin-like and solid, I could now see how truly unearthly the thing really was. It gave the impression of a performer in a shadow play, its sculpted form gradually giving way to a fuzzy penumbra as its extremities came to their terminal edges.

When the Runner made it halfway across the schoolyard’s adjacent road, an odd impulse stirred in me. Some natural instinct implored me to tamp it down, but before I knew what was happening, I was on my feet, locked in feral pursuit of the figure. I didn’t have the presence of mind to look behind me, but the thumping of worn sneakers told me that Jeremiah was not far behind.

The evening air cooled my quickly dampening skin, but my chest and calves burned hotter than the endless forges and furnaces I had so constantly, so nearly burnt myself on in those days of migrant work. The Runner led us around corner after corner, street after alley, parkway after boulevard, foot after foot after foot. As we beat this wretched path, I had no recourse but drink in every inch of Tennyson. The town stretched upward and forward, twisted, upended back over itself again and again. The red autumntide suburb was rendered an insane and unforgiving hell city, a rusted Dis of the Midwest, brought low by surreptitious decay and the unending burn-smoke-grind of the mill, the plant, the factory, each in its way inhabiting our eyes, our noses, our souls. My senses clouded with visions broken people trying in vain to fix their broken tools, their broken lives. Ghosts of fell hatred whooped their rebel yell across the surrounding plains, quieter now but still audible in every home and heart. Nothing grows here, there is only the waves of fire and steel and the slag refuse that spreads in its wake.

The Runner seemed to meld with this pulsing metropolis of the mind, its feet turning to tread the walls and ceilings, up and around gnarled streetlamps and down manholes that then burst their rank black water high into the starless sky. My chest no longer pounded, but froze entirely as the Runner continued its unending marathon, me and the stranger boy in tow, a lockstep triad tearing our soles to shreds in the darkening night. As we went deeper and deeper into the furthest reaches of this bastard Tennyson, I could take no more. I consumed what final vestiges of strength I could find and began to gain on my target. Feeling that this would be the end of me one way or another, I whipped my arm forward and made to grasp the Runner by the shoulder, its body now all but invisible in the pitch. Whether I succeeded or failed, I am still unsure. But at last my body yielded to its gunfire heartbeat, and the blackness of night washed away into the dark of unconsciousness.

#

I awoke what seemed to be only minutes later, with Jeremiah knelt beside me, shaking my arm anxiously. His face was awash in the pallor of high moonlight, dried tear streaks lining his cheeks.

“Jesus Christ, mister, you really spooked me…”

Breathing heavily, he slumped down beside me. I sat up and looked around. We were back in the town center, on the grass a few feet from the founder’s statue. Its faceless head was beatified against the full moon, and in the darkness its shadow spread over the whole of the town. I wanted to look at the boy, but something in the pit of my gut prevented it. His overwhelming terror was evident in the jagged rhythm of his breath. I put my hand on his back and tried to set a pace by forcing myself to breathe deeply, slowly. After a moment, he matched this and I began to stand.

I tugged Jeremiah by his shoulder and tried to gently pull him to his feet. Still refusing to make eye contact, I offered to hold his hand. He accepted, and we walked in silence together until we reached his mother’s house. I knocked on the door, which promptly opened, shedding an unwelcome glow on the two of us.

“My God, Jeremiah, I’ve been worried sick about you!” Minnie cried, throwing her arms around her son. “Where the hell have you two been?” She straightened and shot me the hardest look I’ve ever received.

“It’s all right, Mama, we was just…” Jeremiah said, trying to contain the shudder in his voice. He straightened his shirt and looked at me. “We were just watching the Runner.”

I wanted to clear my throat and explain, but an ungodly dryness left me with a barren, pathetic cough. I wish I could have done anything more for the kid or his mom, but nothing could help them. Nothing could help me or this town. I gave a weak, shaky nod to the mother and child, then turned and left. Looking back, my roving days were a period marred by regret and cowardice, but no single incident has left such an indelible black mark on my soul as the memory of leaving those two frightened innocents awash in their feeble island of porchlight.

I wobbled back to the highway, barely able to stand, much less walk straight. I made it to the nearest road sign and white-knuckle gripped it, holding my thumb out for oncoming drivers. My hands were growing stiff and dry in the nighttime chill. After about an hour, during which time I had to fight to keep from passing out again, a beaten sedan pulled over, and the driver rolled down his window. He was clean faced, wearing a simple shirt and tie nicer than his car would suggest. He had a new briefcase in his back seat and bore a smile in his eyes.

“You look like hell, friend. Need a lift?” His voice was high and smooth, full of life.

I climbed into the passenger seat and swallowed hard. I needed to run, to feel something familiar and safe, to prove to myself that the world can still be beautiful and that people can forgive so much in the face of inevitable endings. So many years since, I still remember the cracked words falling from my mouth.

“Please, take me west,” I said. “As far as you can go.”

Alexander Forston (he/him) is an Indiana-based writer. His work often explores the fuzzy edges of the real and the unreal, yet never abandons the core of the human heart. His fiction has been featured on The Word’s Faire, and his nonfiction has been featured on Brevity Magazine’s writing blog.

Leave a Reply