Because I believe everyone in the land of the free to be the determiners of their own fates, my children and I, whether imaginary or not, pile into the family wagon. There’s no other reason I’d have a wagon. ‘We are going to Nowhere, Oklahoma’, I declare, which happens to be a real place. When he is not snoozing, Johnny takes in the landscapes on the way, the many cows and soybean fields. Suzy, who is older, says she’s bored. Imaginary or not, kids lack character. It reminded me of my own vacations to Florida.

Parents holding each others eyes open, driving tired, me trying not to peek while mom changed bras in the backseat. Disney World. Epcot Center of Bucky-ball Derangement. Rain-streaked masks of Mickey and Minnie Mouse. Goofy—whatever the hell he was supposed to be—holding hands and singing with the children of the world. I suppose I should admit there was a kind of double-talk. Or code-switching, if you will. When as a runt I’d overhear my father asking my Aunt about family, and took him unquestioningly to mean how the particular individuals who were my cousins were doing. At the time I was too young to realize that by ‘family’ he meant the concept, or else being an honest person he would not have feigned quite so much interest.

My own ideas look at me in a daze, as if wanting something, anything, to happen. It is, after all, a long and hypothetically convoluted drive from Somewhere to Nowhere. ‘Soon’, I tell them, ‘and when we get there you’ll see a chasm, vaster and darker than any you could imagine’. ‘Like the night sky?’ Johnny chimes in. Not really. ‘The chasm leads to nowhere, but you will only understand when you are older—when you have ideas of your own.’ ‘Is that sustainable, like in the long run?’ Suzy asked, as though she were part of the conversation. ‘Sure. Ideas don’t take up space, they don’t need food or a place to live, so there can be as many as you like. They don’t get depressed. They don’t ever find themselves jobless, as they can always be, to paraphrase John Locke, employed by the mind’. Suzy smiled meekly. If an idea is really bad it gets thrown into the chasm and is forgotten forever, I thought to tell them, a white lie.

As happens on family trips, I wanted to challenge them. Much as my father before me had lectured in the hotel room till he was blue in the face, about the various ‘do’s and don’ts’, which, being children and not ideas, we did not understand. Regardless, there must be some exact point where they learn to be individuals, and what better time than at the height of the blistering afternoon? So I pulled over and stopped the car, close to the chasm, but not so close that if I backed up or went forward the car was in any real danger. Parallel parking was obviously out of the question. Everyone ‘got out’ of the car. Johnny and Suzy floated forward together, nearing the edge. I wondered what might happen if they hovered over the abyss. ‘Well, kids, what do you see?’ I asked. Their mother wasn’t there, of course, because my children were immaculate. I goaded them on, because they were also fearless.

I wanted to ask them. There have been too many occasions when I’ve seen photos of friends’ children at maybe 3 or 4 months old, at that time when the begin to perceive events, to gain object permanence, or ideé fixe, as the French call it. I wanted to know what object permanence meant when confronted with the void, even if my children were older. ‘I don’t see anything’, Johnny said. ‘I think I see…Grandpa?’ Suzy said, but in a way that was appropriate to her age: part assertion, part question. They were both right, of course, and it remained to tell them they were both right. That is how ideas learn and grow. It is how they branch out from that initial confidence which treats any premise, no matter how unguarded, as a received truth, as something so obvious no one has a right to question it. Johnny was of course right because the void of life contains nothing. There are no bedtime monsters there, just whatever is unknown. We need posit no dark forces to mask our innate fears. Suzy was also right, in that in some inexplicable way we ourselves, our progenitors and progeny—including Grandpa—spring from this nothingness. Whether thought or person graces it doesn’t matter, only that momentarily we can be aware of the fact; just as small human children might have the fleeting awareness of that moment they are released from the fictive depths of plastic gondolas careening imposture curvatures of too serenely perfect blue and white paper waves.

I had wanted to ‘teach’ this moment, not as a lifelong moral, but as a sort of existential proof: that there is a moment, perhaps ephemeral, perhaps forceful, when you wake up. To teach it, in some form or another, if only to understand that I myself had grasped it (was I turning into my own father?). Whether autodidact or poor man’s Socrates, who could tell the difference?

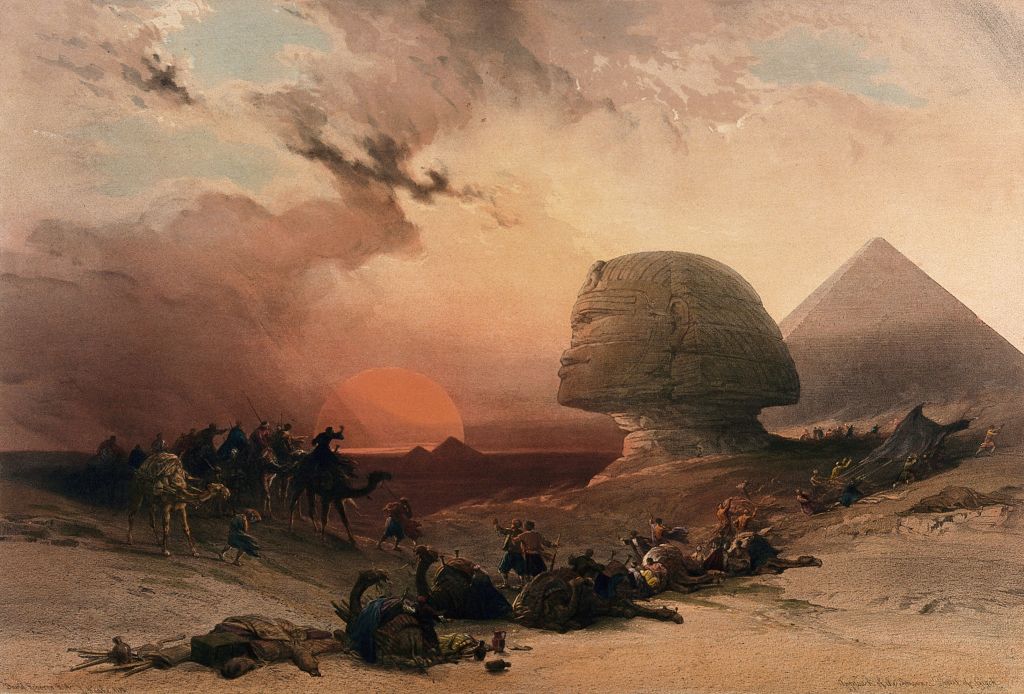

Then the abyss fell forward at my feet. Its shadows were small. I felt like the French soldier in the apocryphal anecdote who shot the nose off of the Sphinx at Giza. It had been there so long. Then this man comes along at high noon and takes out his petty worries on it, a historical artifact that predates his entire culture. I imagine him as a sort of petulant lover, similar to myself, overly aggressive with his cannon, after having been cheated on so many times by his lover in old Provence. Pushed to do it. Falling, crumbling, his worries dashed into limestone, come to rest in desert air. That’s the thing about ideas. They seek rarefication, distinction. They always move just a bit ahead of whoever thinks them, and if you’re lucky, I suppose they acquire a life of their own; you remember them, but you let them go all the same. They are the contrary of water, the water of the Nile which seeps into moist soil, nourishes new life. The differences you appreciate in the void.

*

—‘Sweetie, it’s okay, it was just a nightmare’, my mother had said, after I ran to her bedroom and crawled under the sheets. My nightmares in those days were so vivid that they would seem to be waking. I carried them with me as I fled towards comfort, a familiar voice, an internal monologue yet to be formed which was immune to their world. In those dreams an inarticulate terror suddenly filled my mind, everything living vanished, was blanked out, as though asphyxiated. Being lost and being forgotten were the same. There in the flashing, directionless void, not the least compelling idea could pull you out, or even try. In the waking nightmares that were the premonitions of a life spent writing, Johnny and Suzy were nowhere to be seen.

David Capps is a philosophy professor and writer living in New Haven, CT. He is the author of six chapbooks: Poems from the First Voyage (The Nasiona Press, 2019), A Non-Grecian Non-Urn (Yavanika Press, 2019), Colossi (Kelsay Books, 2020), On the Great Duration of Life (Schism Neuronics, 2023), Fever in Bodrum (Bottlecap Press, 2024), and Wheatfield with Reaper (Akinoga Press, 2024). His latest work is featured in Midnight Chem, The Classical Outlook, and OxMag.

Leave a Reply