I go there to get money, and that is all. I would have a coffee there, but all the cafes are closed. I would have a drink there, but all the drinking is done in private, down in basement apartments or from stone window sills above, by forgotten nobility (two degrees removed) and moldy hunchbacks.

There is a Geldautomat in an alley there. It is the only one I visit. It seems somehow that all the others, colored brightly and located in lively squares and busy streets, are untrustworthy. Their faces are flashing, somehow deceptive. I take out a few big bills every week, sometimes less frequently, from this machine in the alley off Rembrandtstrasse because the whole of Vienna has forgotten about its existence (not in the same open way they seem to have forgotten the gargantuan Nazi flak tower down the street in Augarten park, under which the whole Innerestadt goes to sun itself and skip in circles on Sundays—a kind of open forgetting, ein Vergessen im Freien). They have simply forgotten it, which is to say, it is not within their sight. I trust the machine with my money. When the Viennese see me emerge from the shadows with glowing bills popping out of my back pocket, they scurry like rats hit by rays of light. They don’t know how I keep getting money from within that dark corridor. They even pretend to themselves that they do not know what money is, rubbing their foreheads in consternation. They take 50€ notes out of their wallets and throw them in the Donaukanal to float, golden, with the freshly fallen leaves, spitting under their breath. (I’ve seen it.)

But recently I have been ending up on Rembrandtstrasse even when I do not need money. Just a few mornings ago, I laced up my shoes and went out the door for a walk. I went down every street except Rembrandtstrasse, gulping down fresh air (the fresh air here is always a little moldy, like good blue cheese). I walked under ringing church bells and over wet cobblestones. Cool breezes guided me this way and that. I hopped onto a bench and stared at the sky. I moved from the bench down onto a low stone ledge and watched clouds cut themselves open on green and black spires. I got up and wound down some of the wide Gasses and Strasses, eyed the people as they toasted and drank, or ate mouthfuls of pasta and sausage—and then before I knew it, I was standing on a little bridge, not a soul in sight, looking into the gritted cast-iron mouth of Rembrandtstrasse.

Looking into the opening of this street was like looking into the hard pencil lines of a perspectival exercise, except the artist or draftsman, instead of adding texture and gradients of shade, has only repeated the lines until an accumulation of graphite was left, standing off the paper, reflecting quicksilver light into the closed atmosphere of its own body.

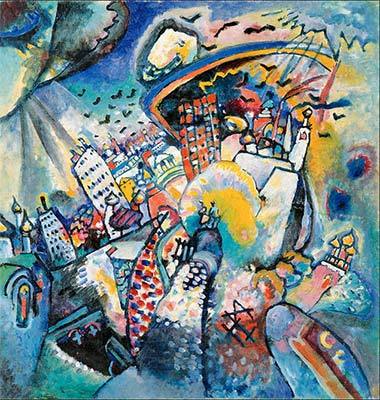

Eventually, colors arise between huge facade-squares of dark gray: deadish blues and waxy yellows. As I went down, I began to look more closely than I had before at the ground floors. Each building was perfectly tessellated together with the next. It almost looked as if the walls and vaulted windows were composed solely of paint, any structural, load-bearing material having been corroded and replaced by layer upon layer of pigment decades before. The colors turned inward on themselves, leaving the street an empty magnitude, like the smooth shores of certain pseudo-surrealists before the waste of the spirit has been tossed pell-mell unto them.

It is always noon on Rembrandtstrasse, but there is no sunlight and the shadows that fall over their objects negate themselves so that all one sees under an eave, or a streetlamp suspended by wires, is a ridiculous material oscillation. Materiality and metaphysics pass into one another so easily on Rembrandtstrasse that standing there in front of the dead Cafe Lambada, hands stuffed into pockets, one understands how a group like Vienna’s logical positivists could arise, the same way a fungus or a disease arises because the area or body on and in which it develops is too clean. Of course, this sheer materiality hides a deep metaphysical compulsion. Rembrandtstrasse is a purely verifiable street—and as a result one begins to believe in phantoms and ghouls lurking behind its every line (there are no curves there except for those that can sometimes be seen behind dusty window panes—the forms of preserved women of the world of yesterday drawn thin by amnesia and hunchbacks craning to catch a glimpse of their bodies).

Just as the positivism of the street passes into the wildest metaphysical gloom, so its noon switches to midnight like two electrons trading charges, two drunken soldiers trading uniform and rank under cover of night.

I cannot imagine the end of Rembrandtstrasse, just as I cannot imagine what it would mean to enter a vanishing point in a representation of space. One looks up after a few strange steps and is then somewhere very different, perhaps on the edge of the Danube or in an enclosed square dotted by sealed windows and the theoretical gazes of unseen residents wavering in the air.

Zane Perdue writes COM-POSIT and has had work published with The Decadent Review, The Hong Kong Review, Ghost City Press, SORTES and elsewhere.

Leave a Reply