“Wyatt, wait, I hear you, I hear you evr’y time,” Poole cooed while Wyatt dipped his index and thumb into the myrrh, then rubbed the slick over his smooth, collarbone skin. Everyone in the church heard the ringing as he traced Inanna’s sigil over the hearth and forest of his chest. “The bells,” Wyatt pleaded as the women in the church combed their hair and flooded their vision with their neighbors and their children at their sides. The quiet night pulsed between his sobs. “They ring, and no one hears’me!” Wyatt flailed and spat, his eyes glassed and wild with firelight. Tugging at the collar of his shirt, he writhed in pain with screams deep from the root of him, the singing myrrh-oil dancing in the candlelight, “He’ll kill’me, he’s out’ta git me, and he’ll kill’me, preacher.”

“No one’s out’ta git you, Wyatt, I hear you, but no one’s tryna kill you,” Poole watched. His eyes followed Wyatt to the earth as he turned to lie on the ground, pushing his back flush to the dirt-rubbed planks while he kicked his feet – drawing lines in the grit where his feet dragged. Blood pulsed the whites of his eyes as Wyatt grabbed at his belt loops, rising and raising his waist in slow writhes. Poole watched as Wyatt calmed and the waves of his body slowly stopped, “He tole me I was a destroying angel, preacher. He tole me.”

“You ain’t no destroying angel, Wyatt,” Poole spoke with shallowed breath coming out as a hushed plod, weighted and heavy. The rest of the congregation started their leave by quietly slipping through the pews, making no contestation between the hems of their skirts and the oak. Grabbing their children with soft hands, smoothing the tops of their heads. “I’ve tole you this before, Wyatt, you’s a good man who just needs ta’catch a break. We don’ judge you here ‘n there’s no sense in puttin’ on this whole show. Let’me git you home now, c’mon with me.”

“Ain’t no way, preacher,”

“C’mon, friend, jus come with me. Mary’ll fix you somethin’ nice.”

“I’mma destroying angel, preacher, ‘n that’s it.”

“Ain’t no sense in keepin’ this goin’, Wyatt,” Poole spoke as he helped Wyatt to his feet.

There were dogs just outside the church in the bleak darkness now that the rest of the congregation had gone. All that was left illuminated were the reflective yellow and blue eyeshine from the backs of the dogs’ eyes, studying Wyatt closely. “Can I rile them up instead?”

“You cain’t have them dogs, Wyatt, leave ‘em alone.”

“I’m bloodthirsty, preacher; there’s somethin’ wrong with me.”

Poole stopped, examining Wyatt’s wildness and how the bends of his reeds were already half-snapped. The man he’d known since childhood, once running feral in the plains from dusk ‘til his mamma called, now stood before him, skinny and empty. Whoever was once inside Wyatt had since long gone, and the fire left burning all but turned to black. Wyatt was now a void staring back at him with the moon hanging high above the two like a drink of water.

While walking along the road, Wyatt spotted Carol Ann. The sun had now risen to eleven, and the wet heat blanketed the air in an uprising. “I hadn’t seen you in a minute, pretty girl,”

“Because I ain’t want you to, Wyatt, ain’t your momma teach you that? Don’t bother no girls when they’s alone?”

“I ain’t gonna hurt’chu, Carol Ann. Haven’t I tole you you’ve got eyes to get lost in? The prettiest hips I ever saw,”

“Stop it, Wyatt.”

“Why you still alone? Why haven’t someone snatched you up? Let’s get married, Carol Ann,”

“Because there ain’t no more good men in the church anymore. They all taken, so I’mma stay with my momma‘n help around the house instead,”

Wyatt wiped his jaw with the palms of his fingers, reached to his belt, and felt for the knife he kept wedged there. Loosening the knife free, he unlatched the blade from its handle. Grabbing at Carol Ann’s arm, she turned and now faced him, eyes wide and struggling against the strength of his grip. “You’re hurting me, Wyatt,” she said instinctively before noticing the black well behind his eyes. His breath smelled of stale tobacco and hunger, and their struggle billowed the spoilt sweat from his clothes and skin. Carol Ann noticed how Wyatt went cold with the knife now on her stomach, pinching the fabric of her dress. She let her mind go blank to steady herself, seeing how his gaze went from glassy to vacuous, all life stripped as his shell became bare. His grip around her arm made her hand go numb, and in an effort to free herself, she began to sing.

Wyatt swung the knife back in its handle, pushing it back into the hip of his jeans. Releasing his hold of her arm, they began walking together along the road again. The sun was now full-blaze like a cattle iron on their backs. The burnt trees and shrubs clung to the red-clay dirt as the distance stretched until the sky stopped.

“I ain’t gonna hurt’chu,”

“Thank you, Wyatt.”

After church, Wyatt found Poole outside feeding the dogs and filling their bowls with water from the well pump. His shoes and the hem of his pants were still wet. “I had a dream last night, preacher,”

“Oh yea, what about?” Poole asked as he kept tending to the dogs.

“I had a dream that I was tole to kill Mike Bourner and that I was to do it by getting’ a piece of cloth ‘n dip it into some coal oil and turpentine and plaster it o’er his face and set it on fire to smother’m to death.”

Poole watched as the scene replayed in Wyatt’s eyes like dancers on a stage. Poole saw light in Wyatt’s eyes for the first time in a while. His pupils took on the whole of his baby blues, wiping out any color that was once there, but the bleak void now illumined like a flashlight clicked on. Instead of the vacuous, endless, empty hollow, there was now an effervescent maw gaping back at him. “I won’t do it, though,” he said, smiling.

“Okay, now, Wyatt,” Poole spoke. Reaching to find more to say, with a full bowl of water for the dogs still sitting in his hands like an offering. He instead stretched his other arm to wipe the sweat from his brow. Looking to the dirt and then back to Wyatt, unbridled and gleaming. Poole let his vision blur. “Just don’ tell nobody else.”

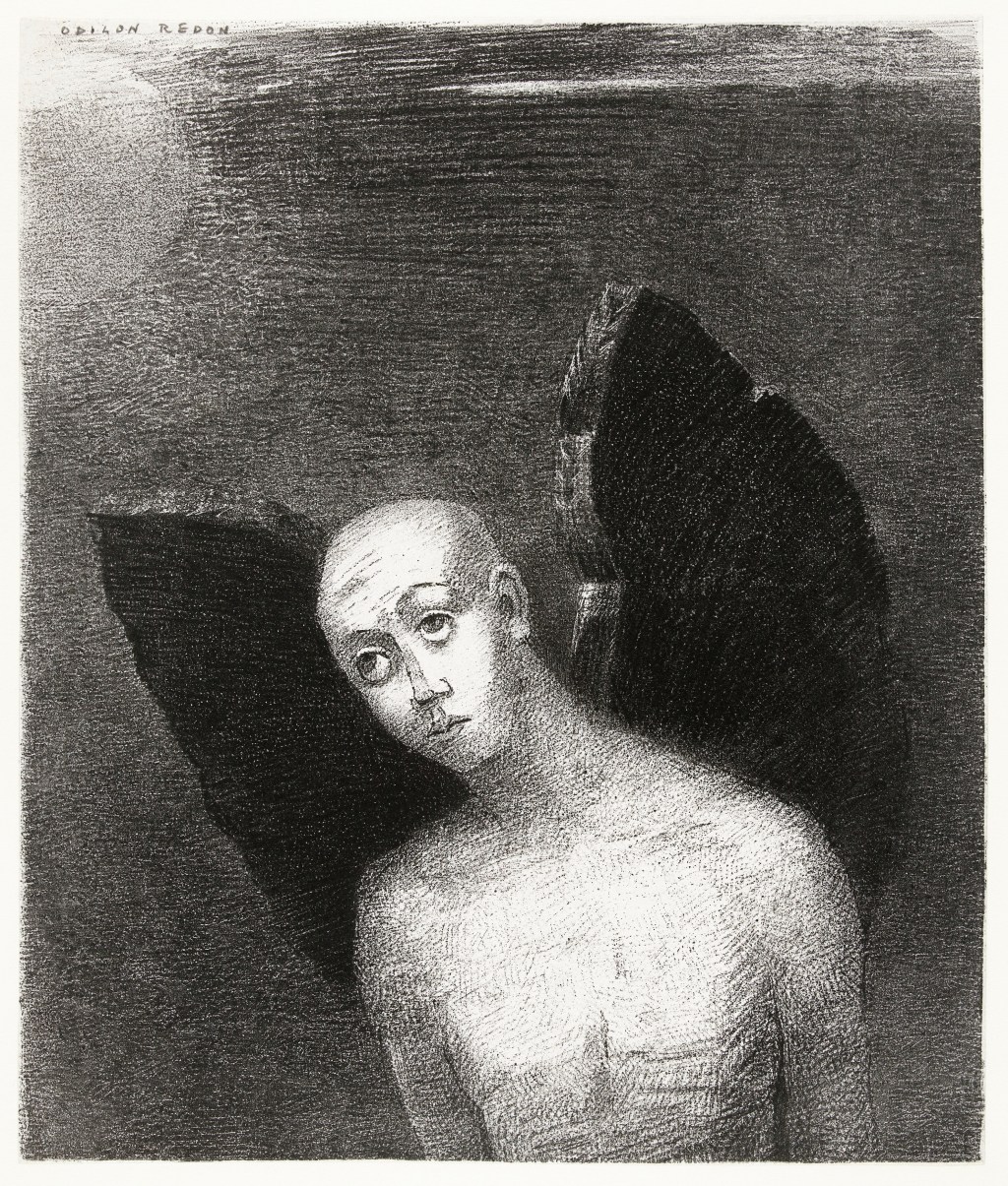

That evening, Wyatt went home to his momma for the first time in a week. Lying on his bed upstairs, his boots and shirt piled in the corner, his momma saw the smallness of his body half covered by the sheet. His shoulder blades stuck out like the nubs of wings cut off. His brown hair tussled like fireworks at night. For once, someone could see Wyatt like the small, frail child he once was. Catching snakes with his bare hands and chasing off any visitors like a caught coyote, here he now was, sleeping in his bed again but in the body of a grown man. The only thing that changed was the height and weight of him.

Wyatt began to rustle awake, turning his body to see his momma standing in the doorway. “What’chu doin there, momma?”

“Nothin’, bunny, just glad you’re home; go back to sleep,” Mary mewed.

Just then, something caught Wyatt’s hold as he slumped his feet to the floor, rubbing the outside of his arm and looking around the room with lowered, swollen eyes. Pulling on his shirt, he reached for his boots and took the knife he set on the dresser back into the hip of his jeans while tightening the loops of his belt to keep it steady.

“Now what’chu doin’ that, for, Wyatt?”

Strings of sentences came bubbling from Wyatt in disconnected draws. As one unintelligible idea came after the next, Wyatt turned to take flight down the stairs with his momma trailing behind him. “Where you goin’? Wyatt, wait, stop,” his momma paused. Watching Wyatt fly out the front door like a cat, his slender body reflecting the moon’s light as he hurried faster. She watched as his body took off in a full sprint toward the wheat fields. The hush of the wind and the song from the cicadas rose with each step as he approached the expansive field of wheat stalks. Once he was close enough, they beckoned him in with soft sighs. Collecting their fluffy tail stalks around his back, they hugged him in close as he collapsed into the reeds with a slump. Staring up at the expanse of the night sky, the sound of the wheat welcoming him crooned overhead – the stars dancing in and out of view.

His momma had turned to go back inside. Climbing the steps, she reached the window of his room that overlooked the wheat fields below. There, she saw him lying in a heap with the light of the moon and the stars pooling in the hollows of his ribs and chest. When the wind swayed in the right way, she could see his face alight with ponds of darkness and skin-white.

Cuddled with the wheat, Wyatt pushed himself to his knees in what his momma thought was prayer. But then Wyatt began to dig into the wheat field, pulling stalks of wheat plum out of the earth in fistfuls. Kissing the clumps of dried wheat, he then arranged them in piles of four or five. Unsure of what to think, Mary phoned for the sheriff to come quickly.

When the sheriff arrived, Wyatt was still out in the field, pulling at the stalks and arranging them in his piles. Beaming from sweat, Wyatt continued his pile-making with the crowd of wheat around him, petting his arms and back in yielding caresses. The sheriff deepened his approach to Wyatt, coming at him in slow steps. Not wanting to scare him off, his softened gait was meant to be tender.

“Son, it’s the sheriff here. I don’t wanna scare you or nothin’, but I wanted you to know that your momma called and told me to come see you here tonight.”

Wyatt stopped mid-pull, glancing at the sheriff close-up behind him.

“Why don’t you come on with me? I ain’t arresting you or nothin’, but come on down with me ‘n we’ll get you set all-right.”

“I don’t wanna go to Linden, sheriff; they’re gon’ kill me there. I’ll need you to go with me and take care of me so they don’ kill me. The sheriff there knows me and is friends with all the other folks there and will let’ em kill me,” Wyatt chattered. The sheriff saw how his body buckled with the moon’s weight on his shoulders. “They ain’t gon’ kill you there, Wyatt. I’ll be sure to let ‘em know not to. They’d have me to answer to anyway. Jus’ c’mon with me, and we’ll let you settle for the night so your momma don’t die of no heart attack with you in this state.”

Later, when Wyatt and the sheriff got to Linden, the night turned to its blackest state. In the hours just before dawn, the deepest parts of the sky came on. The depths of blue-black were deafening. “Please don’ leave me, sheriff,” Wyatt pleaded, “they’re gon’ kill me,” as the sheriff and the deputies from Linden put Wyatt in a cell. “Please stay with me, or come in here and lock all the doors ‘n fasten down the windows. I cain’t stay here by myself, sheriff,” Wyatt called. The sheriff now backing out of the room where the cells were held and toward the door. “Axes and razors don’ fuss as much as you, Wyatt.”

Slinking to a corner of his cell, Wyatt began to rock. Holding his knees close to his chest, he cradled his head to his forearms while swaying on the heels of his boots. “My head feels light. It feels heavy and tight and pressed,” he sang, crowing to the tears as they sank along his cheek.

A.N. Kersey is a short story author and poet from Dallas, Texas. She spends most of her time in academia, while the rest is doled out among various hobbies, such as guitar, writing poetry in her Notes app, and wistfully researching niche interests that annoy all those around her. She’s fun at parties, except when someone brings up said researched niche interests. That’s when she finds it’s best to keep her found nuggets of wisdom to the confines of academia and her writing.

Leave a Reply