How we met

William McGonagall almost knocked my husband off our hotel bed.

I must have heard of him before that evening in 2017, but I didn’t know his story. To begin again: Sir William Topaz McGonagall (1825-1902) is most commonly known as the worst poet in the English language. He was openly ridiculed during his lifetime. His alleged knighthood – Sir William Topaz McGonagall, Grand Knight of the Holy Order of the White Elephant, Burma – was somebody’s idea of a joke, but he was apparently taken in by it and published under that name. Newspapers mocked him, but he was so very earnest about his work. He may have been on what we now call the spectrum; fetal alcohol syndrome might explain a lot. In his later years, he was hired by theatres to recite his poetry while the audience threw food at him. Since then, he’s served as the punchline of dozens of jokes, in scholarship and the arts. But we create the reality we want to believe in.

To begin again: I imagine him happy. I imagine him loved.

Hotels

I should explain. It was one of the hotels overlooking Waverley Train Station in Edinburgh. We’ve stayed in a few while visiting my family, so they blend together. One was very high tech, with room controls in a touchpad on the headboard, so any active sleeper is liable to be woken up at 3am by turning on the lights, coffee maker, and trouser press. That might also have been the one that had a bathroom with glass walls, frosted to about shoulder height and clear above, so you could peer out at the bed if you felt that way inclined. My husband and I had been together for years by then, but we still came up with a code for when we needed privacy:

“Wouldn’t you like to go and have a cup of tea in the lobby, my sweet?”

“Yes, I’d love to. Shall I take my phone with me, so you can let me know when I’m finished?”

Not that one, on second thought, as we had the kid with us. It must have been a normal, forgettable room. I do remember great views of Calton Hill, all lit up at night, and it was handy for a fabulous wee French restaurant I won’t name here, as it’s far nicer when there’s nobody else there, and you wouldn’t like the food anyway.

We were going to visit Greyfriars Kirkyard the next day, and my husband was looking up the people buried there. He was already crying with laughter and almost falling off the bed by the time he started reading us the online description of the poet who has since claimed a space in our hearts. Things like these are important. As I began to write this, in February 2022, the pandemic seemed to be winding down, but the American economy was in freefall, and things were kicking off in Ukraine. My fiction notebook was full of ideas about ugly people and things, but this was the story I wanted to weave together in that moment.

William McGonagall

When we got home to North Carolina from that trip, we ordered a copy of The Autobiography of Sir William Topaz McGonagall, which gives the main details of his life, some of which were then fleshed out in later publications. He was probably born in Edinburgh; his parents were Irish. He received his basic education, then became something of an autodidact. As an adult, he followed his father into the weaving trade. Unfortunately, weaving was one of the first victims of the Industrial Revolution, with work being done more efficiently by automated looms, at home and abroad.

He also tried acting. One of the earliest anecdotes in his autobiography is about raising funds among his coworkers to put on and star in a performance of Macbeth, during which he refused to die and had the crowd cheering for more. He informs the reader that the rest of the actors were jealous of his success. He had no doubt about his talent.

Then in June 1877, when he was 52, the Poetic Muse appeared to him and compelled him to write. And from that day on, he was a Poet – capital P, and that’s how he listed himself in the 1881 census. He wrote tributes to friends and places and edifying verses about current events and the ills of society (mainly caused by the Demon Drink – he was a Temperance man). The thread tying all of these works together was the fact that things rhymed. Forget meter, metaphor, or any other concerns; if the end of the line rhymed, it was Poetry.

His next adventure was when he went to visit Queen Victoria. He had sent her some of his work and received a card in response from a secretary, politely refusing to acknowledge the gift. Undeterred, he walked from Dundee to Balmoral – a journey of several days – in order to present himself to Her Majesty. It went as well as you’d expect; he trudged through a storm only to be threatened with arrest at the gate. Everyone who writes about him seems to delight in that fact. But here’s the thing: he says the landlady he stayed with on the first night was welcoming and gave him water to wash his feet after his long walk. The second night, he was taken in by a shepherd and his wife. They fed him and listened to him recite his poetry as he dried out by the fire. More people gave him shelter as he walked back to Dundee, even providing food for his trek. These are the people I wish we knew more about. He describes them as listening in rapt admiration and treating him with great courtesy. Surely, they were just being kind to him. Isn’t that what any of us should do when faced with an earnest, harmless soul?

Cupar

On our next trip back to Scotland, my husband and I did a proper twilight wander around Cupar, where many of my relatives now live. You’ll only have heard of Cupar if you’ve failed to get lodging in St. Andrews – 9.5 miles away – during the Open. It was winter, and at that latitude, if you miss the window of daylight that lasts from approximately 8:47am to 3:18pm, then damn and blast, there’s nothing left to do but go to the pub. Damn and blast, I say.

Before visiting our usual spot for a sampling of flavored gins, we hit all the town’s highlights: the butcher’s shop with trays of fresh haggis and sausages; the fishmonger to see what had arrived with the boats that morning; the fancy booze shop that also sells fancy cheese; and the tiny book shop that improbably exists on a narrow, one-way street with no gaps between the buildings. It looks as if it used to be somebody’s house. We did our usual trick of pretending we weren’t going to buy anything that would have to be crammed into our suitcases. We also have different tastes in books, so I was in the fiction section, smiling hello at my old friends on the shelves, when my husband came across the room, clutching a thick volume: William McGonagall: Collected Poems, with an introduction by Chris Hunt and including a second version of McGonagall’s autobiography.

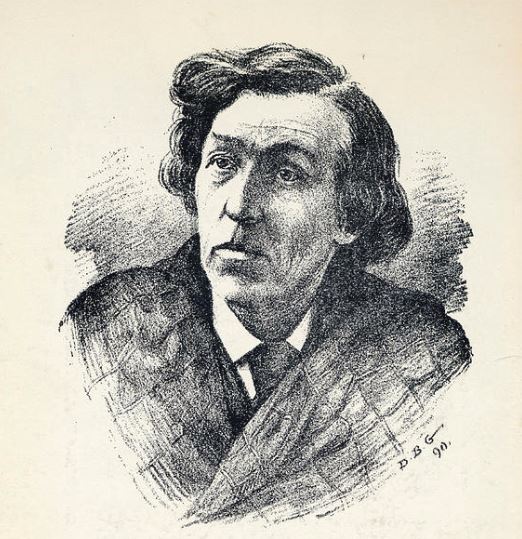

We immediately went straight home after a few swift rounds of gin to show our spoils to the family. One very clever relative took one look at the photo of McGonagall on the cover and said, “Fetal alcohol syndrome.” Sure enough, according to Google, a smooth or indistinct philtrum (the bit between the nose and mouth) and a thin upper lip can indicate that condition. Other symptoms include intellectual and developmental issues, poor judgment, and hyperactivity. Some commentators speculate McGonagall was playing the fool and wasn’t really a bad poet, but who would fake those traits throughout their life? I don’t buy it.

Research

My first stop for any scholarly project is the databases available through my university library. If you’ve felt the urge to look McGonagall up anywhere, you’ll have discovered that a lot has been written about J. K. Rowling’s character, Professor McGonagall, so that complicated things. Rowling also apparently did a lot of her work in The Elephant House café in Edinburgh, which is a delightful coincidence.

A few articles address the correct McGonagall. The ones I read simply mocked him, but one mentioned William Power, whose book called My Scotland looked worth tracking down. I then requested a copy of David Phillips’ biography, No Poets’ Corner in the Abbey (1971), written with the benefit of full access to the Dundee library collection of McGonagall documents. It gives great insight into life in his day, listing current events that might have inspired more McGonagall works, from body snatcher crimes to visits from dignitaries. It’s also filled with meticulous details about wages, prices, and rents for the average weaver in the city, called “Juteopolis” by its inhabitants back then. Times were hard; industrialization and the outsourcing of labor overseas combined to make life especially difficult for the working class. Phillips notes the years when the poor houses were full and the trends in arrests for drunken and violent behavior. He also gives background on McGonagall’s family – the fights his son got into, his daughter’s drinking. He uses a particularly Scottish phrase to describe McGonagall: “poor soul.” This was a step up from the more academic sources.

However, it made me rethink my image of McGonagall as a happy man. As I said, the alternative is a more cynical theory that he was playing a role, like a clever actor making a fortune by playing the fool, but his final years don’t fit that narrative. Phillips includes copies of the letters McGonagall sent to potential benefactors during his lengthy illnesses. He was literally begging for help, but the tone of the biography doesn’t take that any more seriously than it does the fanciful scenes of Queen Victoria chatting with John Brown. Phillips imagines neighbors laughing at McGonagall. He claims to see a peasant Irish legacy in the man’s face. To his credit, he does criticize those who played jokes on the poet: “none of them seemed to feel the slightest responsibility for even seeing that he was let down gently, that some of his more essential needs should be met now and then, even if they no longer wished to pay him sniggering adulation.” Phillips also says McGonagall was treated “like an amusing, but cheap, toy, to be thrown out with other rubbish when broken” – but the way he wrote about my beloved poet still made me sad. McGonagall’s poverty and hopelessness were the same as those of countless other men and women who struggled to feed their children, but he also appears to have been utterly defenseless against the (more privileged) jokers of his day and against the scholars who were still laughing at him into the next century.

My husband and I decided we would visit the Dundee collection one day when we went over to Scotland the next May. We would cross the silv’ry river Tay on our way. Which none can gainsay. (see “You Too can Be a Poet,” below)

The film

While reading Phillips, I also watched The Great McGonagall (1975). Spike Milligan cowrote it with Joseph McGrath and played the eponymous hero, and Peter Sellers played Queen Victoria. It begins with the actors having their makeup applied, then the cast walk onto the set. We see McGonagall being struck by the Muse in his shabby home. He performs Macbeth; he walks to Balmoral. There’s a hallucination about Queen Victoria playing piano and various Hitler gags. The actors break out of a scene to talk about how to play it. There’s an intermission with a group of actors in full costume eating lunch at a picnic table. It’s absurd, which many people like. Milligan later co-wrote at least one book about McGonagall, which I found to be “fucking gibberish” – that’s all I wrote about it in my notebook, and I can’t even remember why. I don’t see why it had to include McGonagall at all, when the artists were perfectly happy creating characters for their other works. Inspiration for art clearly strikes in different ways.

The Tay Bridge Disaster

The first rail bridge over the Tay, linking Dundee with Fife, opened in 1878. On 28th December 1879, high winds (potentially with hurricane speeds, though the record is sketchy) brought the bridge down, along with a train that was crossing on its way north from Edinburgh. Everyone on board died, at least seventy people, judging by a combination of tickets sold and testimony at the following inquest. Tragic though it was, this disaster led McGonagall to one of his greatest works.

I can’t include the full poem here, so do a quick internet search for “The Tay Bridge Disaster.” It looks like poetry, right? See those declamatory exclamation marks and apostrophes! But if you count the beats, the apostrophes don’t achieve anything. The lines don’t have a regular number of beats anyway, so shortening those words is pointless. The verses also have different numbers of lines. Some poets do that for effect, to make the verses create a shape on the page or to rebel against convention. I’m not sure that’s what McGonagall was doing. And the theory that he was playing the fool falls apart again here. It ends with “For the stronger we our houses do build / The less chance we have of being killed,” which is pretty clunky. He also does things like rhyming “buttresses” with “confesses” while explaining that the construction of the bridge didn’t take weather conditions into account. I just can’t accept the idea that any reasonable person would make light of this terrible loss of life to keep up some kind of court jester act.

Chris Hunt also points out that McGonagall’s poetry got better, formally, as he aged; if it had been an act, it should have got worse to increase its appeal. And McGonagall had an audience he could have worked with, had it been a ruse. Students in particular liked to play pranks on him, pretending to book performances or sending him on wild goose chases. Again, that knighthood by the King of Burma was a joke, perhaps one that McGonagall persuaded himself to believe in. He included the full letter the wags had sent him in his autobiographies. Other jibes were less severe but no more dignified (McGonagall wrote, “the first man who threw peas at me was a publican…”), or more dignified but also more public (a newspaper responded when he threatened to leave Dundee in 1893 that he would surely stay at least until the end of the year for the sake of the rhyme).

Sometimes, McGonagall was wise to his tormentors. Here’s how he describes one encounter, in which people had pretended a famous actor wanted to meet him: “I kept silent, and I stared the rest of my pretended friends out of countenance until they couldn’t endure the penetrating glance of my poetic eye, so they arose and left me alone in my glory.” I truly believe McGonagall thought he was powerfully gifted and could prevent harm with his poems. It was his responsibility as a Poet.

You Too can Be a Poet

Again, according to McGonagall’s Muse, all a poem has to do is rhyme. How much more egalitarian could a mode of expression be? It’s the most accessible art form imaginable. Try this experiment: what did you have for lunch yesterday? If it wasn’t an orange, you can now make up a poem about it. Isn’t that empowering?* Once you’ve given this a couple of tries, the real trick is to try and stop making things into poems. (does this explain “Research,” above?)

*My husband insists I tell you to look up a video online in which Eminem rhymes things with “orange.”

William Power’s book

William Power’s My Scotland was a joy, after it made its way to me from the University of Texas Libraries, though I’m wary of committing to an opinion of anything written in 1934. Power mentions Messrs. Hitler and Mussolini in passing, so for fear of praising someone who may not have been on the right side of everything, I’ll limit my comments to his writing – which is dry and amusing and thoughtful. For a work of history, it’s very accessible and paints a quite lovely picture of Scotland at times, without falling into the trap of being overly idealistic.

Most relevant is the chapter on “Poetry, the True and the False.” He says he once saw McGonagall in Highland dress, reciting his poetry and selections from Shakespeare during a performance in Glasgow while being heckled and having fruit thrown at him, much of which he smote with his costume sword, leaving him covered in orange juice. Power says he “left the hall early, saddened and disgusted.” That’s more like it – a commentator with a heart.

Not all of McGonagall’s appearances were so ignoble. Power tells us that while in Edinburgh before that evening’s performance, the bard “informed his entertainers that Shakespeare and Burns were no more than his equals.” Power was also aware of the debate about McGonagall’s “true” character, so people were obviously theorizing about him even then. Power says he thinks it was a pose to begin with, and continued because it was successful, but that by the end, McGonagall was “the victim of his own invention.” He continues,

“He was a decent-living old man, with a kindly dignity that, while it need not have forbidden the genial raillery that his pretensions and compositions provoked, ought to have prevented the cruel baiting to which he was subjected by cruel ignoramuses.”

Power says McGonagall exhibited “a fury which I fancy was not wholly feigned” when he was pelted with food. That could mean that his character had got out of hand, and he was angry at the hole he’d dug himself into. Perhaps he felt the indignity of what he was doing. On the other hand, if he was that clever, why not call the gag off? After his travels to London and New York (see below), not to mention his time in mills and pubs, he could have removed the mask and brought the refined audiences of the day along with him as he forged a new persona. I want to believe he was genuine, so I can keep feeling positive things about him – even if that means his life really was sad.

Mr. Alexander Lamb

Alexander Crawford Lamb (1843-1897) is a bright spot in this story. He founded a Temperance Hotel in Dundee, so he and McGonagall shared a desire to improve the lot of their neighbors. He was also voraciously interested in the history and architecture of the area, compiling an impressive collection of documents and artworks that are currently housed in the City’s Museum and elsewhere. More importantly, he took McGonagall under his wing, either as a talented poet or as a human being in distress. I choose the latter, because I want to.

McGonagall in New York

McGonagall crossed the Atlantic in 1887, having been persuaded by alleged well-wishers that he would conquer the continent, starting in New York. Undaunted by an unsuccessful trip to London in 1880, he bought a steerage ticket on the Circassia. Unfortunately, Americans were actively boycotting all things British at that time; no wonder McGonagall tells us Lamb called those well-wishers “pretended friends” and told McGonagall to let him know when he wanted to come home.

Here’s how I imagine the scene as he arrived at the house of some acquaintances in New York.

Dingy parlor interior, ground floor of a tenement building; a small fire in the grate smokes into the room. There’s a knock at the front door, down a short passageway. A Man in vaguely old-fashioned clothes opens it. McGonagall is striking a Pose. Travelling cape, large hat, cane.

Man: silence

McGonagall: It is I, McGonagall, the Poet!

Man: Oh.

Woman [from kitchen]: Who is it?

Man [over shoulder]: William McGonagall.

McGonagall [continues striking that Pose]

Woman [approaching, wiping hands on apron]: Och, if you’re no going to tell me – oh.

They would have had to invite him in. They would have had to half-listen as he regaled them with the story of his passage and his plans for the trip. There must have been meaningful looks between them. How could there not have been? They must have had to laugh until they couldn’t breathe as soon as they were alone, repeatedly whispering the 1887 equivalent of “what the actual fuck do we do with him?” They would have had to feel guilty but laugh anyway as they processed their worst thoughts together, because that’s what marriage is – having someone to be your absolute worst self with, because you can’t be that person with anyone else.

McGonagall didn’t stay for long. He tells us he cried as he wrote to Lamb, who sent him a second-class ticket (better than steerage) and £6. McGonagall had only expected £3.

Dundee

My husband and I did take the train from Cupar to Dundee in May 2023, a journey of about 25 minutes. The Tay Bridge is a slower part of the journey, with the train taking just under four minutes to cross the impressive river. The water was more of a Carolina Blue than silver, as the weather was simply glorious (we had believed the forecasts and packed woolen sweaters rather than t-shirts; live and learn). We walked from the station through the shopping streets to the library, a beautiful, modern building. The archive room is upstairs, with lots of windows and big tables, so scholars like us can spread out. The nice woman who checked our IDs asked, “What brings you to McGonagall?,” as if his folders aren’t requested very often, and she was a bit pleased to dust them off. We spent an hour leafing through two small, 3-ring binders of letters and mementoes in plastic holders. Some were copies, but most were original and signed with his beautiful signature, followed by the word Poet. Underlined.

I took pictures of the ones that were asking people such as Lamb (“my dear friend”) for money to pay his rent or get a collection of poems printed, which

turned out to be the bulk of them. He also wrote to James Shand, on 18th June 1902, to inform him that his daughter had died at the age of 30. A sad flourish fills the bottom of the page.

One of the last documents was an advertisement for his son, William McGonagall the Younger, who was going to do a reading of his father’s poetry alongside “other great poets” like Shakespeare and Tennyson. In fairly large type, and with pointy finger illustrations on either side, it states, “All should see him before the Cholera arrives!” Covid gave us all some insight into that kind of consideration.

When we left the library, we headed in the wrong direction and quickly decided to turn back rather than exploring further; not all of the city has been gentrified. But a couple of pints and a smashing plate of fish and chips followed by a tour of HMS Discovery rounded the day out nicely. Slight cloud cover made the Tay undulate like molten silver while rain fell on the hills in the distance as the train made its way back over the bridge, safe and sound.

McGonagall and Lamb

Power describes Mr. Lamb as a kind man. I can’t help but imagine a scene between them during McGonagall’s many years of illness; he suffered from poor diet and a variety of ailments that seem to have just needed basic care. I don’t know how Lamb himself died in 1897, but it happened in London. Perhaps he knew he’d be leaving McGonagall behind.

Bedroom interior, sparsely furnished. Weak afternoon light. McGonagall in bed; shabby white nightshirt, stubbly. Lamb sits on a plain wooden chair by the window. They have chatted about this and that; Lamb is staring at the wooden floor. After a pause:

WM: I worry about my elephant.

AL: [only moves his eyes to look at him] Your..?

WM: [clarifying] Elephant.

AL: Yes?

WM: His Majesty King Theebaw of Burma and the Andaman Islands elevated me to the rank of Keeper of the White Elephant for my contributions to literature.

AL: Mmm.

WM: You’ve read the letter.

AL: Indeed, I have.

WM: How long do elephants live, I wonder?

AL: [looks at WM, makes a decision] Many years. Longer than a man.

WM: Mine must be past the prime of life by now.

AL: I have read of such ceremonial creatures. Elephants, camels, llamas. Upon completing their great service, they retire. They become lazy and enjoy their leisure. They have food and shelter to the end of their days, and keepers to care for them.

WM: [stares at the sky visible above the tenement over the road] Longer than a man…

AL: And the keepers’ sons take up the mantle, when the time comes.

WM: [sighs contentedly]

AL: [rises, puts on his hat, takes WM’s hand] They consider it their greatest privilege, William, to keep these gentle, noble beasts from harm. [exit]

Edinburgh

After Dundee, we spent a few days with family in Inverness (and spotted McGonagall in a coffee table book about whisky), then we went back to Edinburgh. We spent our last day of the trip on another quest, returning first to Greyfriars, so I could take pictures of the handsome black and gold plaque that marks McGonagall’s place in the paupers’ grave; it even has his picture, which is nice to see. It was another glorious, sunny day, so we hydrated responsibly with a pint before going to another of our haunts for another pint (just to be sure) before setting off to find McGonagall’s last home, on South College Street. It’s a fairly long, cobbled street of uninterrupted 4-5-story grey stone buildings. Another black and gold marker is above the front door of the building his small flat was in, with that same portrait of him.

As luck would have it, a pub is now next door. It’s a one-room establishment – bar on the right, seats on the left, toilets at the far end – and it has musicians. It was hard to tell which ones were there professionally, or how formal the arrangement was, but at least four men had a variety of guitars and those hand-held drum things, and they were running through folk tunes, Buddy Holly songs, and whatever else they thought people might sing along to. Whenever a punter came in, they asked what they would contribute. A middle-aged woman sang a couple of Brazilian songs a cappella. A young man from Chile played “Here, There, and Everywhere.” My husband joined in with an improvised blues shuffle (I just asked him what it was; I had no idea he and the other guitarists were making it up). A young American woman sang some Johnny Cash. Her mother started buying rounds for everyone, and we all got pally in that way you do when you find out that the daughter went to college just down the road from us in North Carolina. It turned into another of the long, boozy adventures we tend to have the night before we fly home, and it was perfect.

Despite the libations, it was also the perfect end to our tribute to McGonagall. All those strangers coming together in the sheer joy and community of expression and music and art. Who says it has to be good? Why was McGonagall a “bad” poet? He tells us he was popular with his audiences, but does that mean they thought his poetry was “good”? Maybe they were celebrating his bravery and his commitment and the moments they were experiencing together, which far outweigh any technical errors. There’s an expression the Scots use for just such an occasion: “gaun yersel!” It means the person is with you in that moment, flaws and all. “Go on, yourself!” It’s a great big fucking yes.

Do what you believe in and believe in what you do, and people will see that. It might not always feel like you love it, but love is just belief over time.

McGonagall’s Elephant

You’re standing on the North Bridge, in the heart of Edinburgh. The bridge connects the Royal Mile and Princes Street, the two main, historic streets of the city, so you’re on the crossbar of a big capital H. Behind you on either side, tourists are walking up Arthur’s Seat and Calton Hill. To your right, the golden sandstone buildings of Princes Street are resplendent in the sun. Over the railing of the bridge, you trace the train tracks running from Waverley Station beneath you toward the Castle on its hill ahead. You turn to your left; there’s music in the distance, and it’s getting closer. The last traffic turns off the road, leaving it clear for the crowd. You walk until you can see over the crest of the Royal Mile. It’s a procession; people are leaning from their windows to watch. There are pipers, dancers, jugglers, and acrobats for as far as you can see. Everything is in technicolor. White petals fall from the clear blue sky. And at the center of it all, acknowledging the crowd with a dignified wave, is William McGonagall, sauntering toward you on a well-fed, happy elephant.

Sources

McGonagall, William. The Autobiography of Sir William Topaz McGonagall. Dodo Press, 2010.

Hunt, Chris. “Introduction” in William McGonagall: Collected Poems. Birlinn, 2006.

Phillips, David. No Poets’ Corner in the Abbey. Duckworth, 1971.

Power, William. My Scotland. The Porpoise Press, 1934.

By Catherine Mainland

Leave a Reply