Herman—who finished his coffee, got out of his desk chair, and put his forehead against the only window in his small attic apartment, and gently, so that his head would not crack the sun-brittled, antiquated glass—was a translator of poetry. That was how he made his living. Feeling himself filled with the poetic spirit, but realizing that his own attempts at composition, in the past and, unfortunately, more recently, had resulted only in exercises and, at the most, novel fragments of a greater, unwritten text (this is how he phrased it to himself), he committed himself to the vocation of translator.

He was working on a prose translation of an ancient poem in a hybridized dialect of two ancient, little known languages.

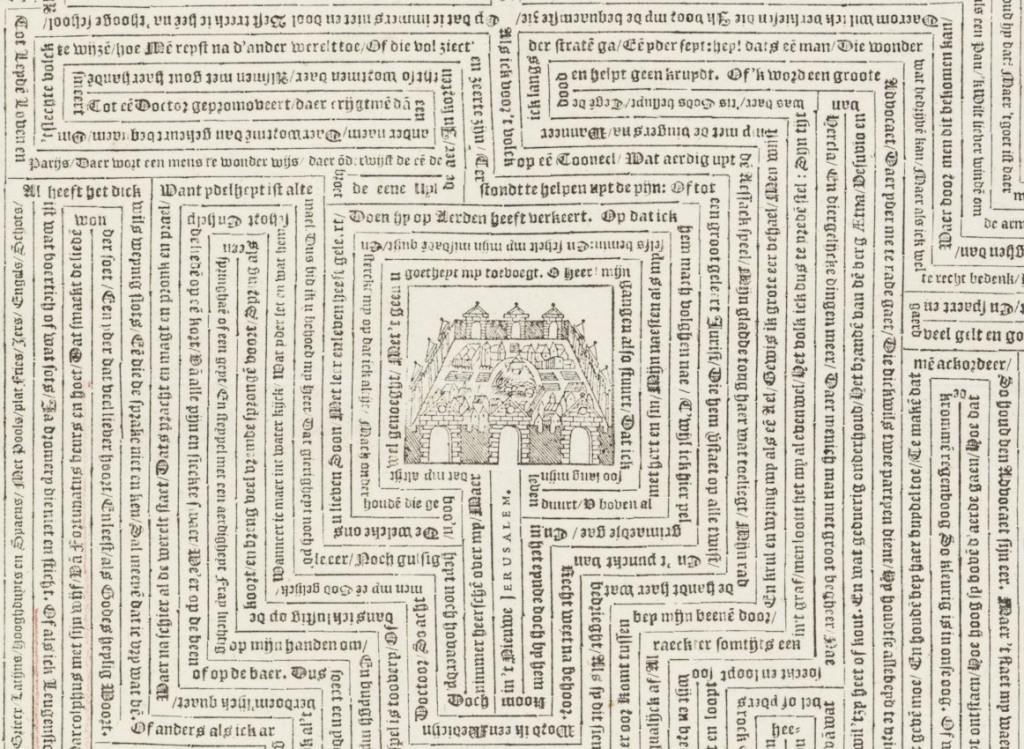

Two weeks into the preliminary work, he decided to go to the town’s archive and request a high-quality facsimile reproduction of the primary manuscript—and to his glad surprise (he was careful not to openly express this), the short gray archivist at the desk gave him the original incunabulum with the sole requirement that Herman check in with the lending office every week. Professional and terse, he agreed, and the manuscript was handed over to him.

The poem was written in a dark red hand on twenty thin sheets of paper made from birch bark. The content would hardly be worth going into here, for there was a specific, essential linguistic problem Herman faced, which might be of interest to the reader.

It was about the title of the poem: this was the impasse to which Herman’s work had recently come because titles, especially in the world of translation, are like magical substances that must be handled with precise alchemical care so that their active essence will not be lost, however much the signifying form must be altered. The title of this poem was given in a single word in the original. In English, it could be correctly translated—but merely correctly, with a bare minimum of correctness—via four words, which were “The Song of Blood.”

Herman found this unacceptable on several counts. The politically dubious association of the word blood (nation, family, race, and so on) were too strong, especially when coupled with song. Further, the multiplication and lexical dispersal of the single, medium-length word of the original into four easy English syllables seemed facile, pseudo-romantic, badly posed: anyone could have done it that way. But the meaning of the title was really inseparable from blood as well as from song, so Herman, after much scratching on his notepad, devised a solution that satisfied the text not only on a linguistic but on a poetic level. Herman’s notes (with minor editorial regularization) are as follows:

Argumentum: Formula for translation of __ (The Song of Blood),

“Lalangue”: an amalgam of libido and signifiers.

Libido = Sex = Drive = Desire = Blood.

Signifiers = Letters = phoneme = sound = Song.

Therefore: Libido = Blood. Signifier = Song … resulting Lalangue = title of poem = X.

Thus: X = an amalgam of blood and song.

Corollary

Blood (libido)

Sanguine, (sang’gwin) a. [Fr. sanguin; L. sanguineus, from sanguis, blood.]

- Red; having the color of blood; a sanguine color or countenance. [Dryden, Milton]

- Abounding with blood; plethoric; a sanguine habit of body. [Technical]

- Warm; ardent; a sanguine temper.

- Confident. He is sanguine in his expectations of success.

Song (signifier)

Song, n. [Sax. song; G. sang, gesang.]

- In general, that which is sung or uttered with musical modulations; a ballad. The songs of a country are characteristic of its manners. Every country has its love songs, its war songs, and its patriotic songs. (This latter entry, crossed out in red by Herman)

- A lay; a strain; a poem. [heavenly felicity.] (And this, underlined by Herman)

- Lamentation, as that of David over the death of Saul and Jonathan.

Solution

Condensation of the two words as: Song [Saxon] + Sanguis [Latin] = Sang

Sang (TITLE): A foreshortening of Sang(uis) pronounced: Song.

And that was how, by way of a poetic, lexical transubstantiation, Herman rather cleverly translated the title of the old poem, subverting the politically dubious, poetically unimaginative rendering already indicated above.

Zane Perdue lives in Philadelphia, PA, where he works at a bookstore. His writing can be found in The Decadent Review, The Hong Kong Review, SORTES (pending), and elsewhere. He is originally from Albuquerque, NM.

Leave a Reply